Robert Zubrin is a persistent man. An engineer, author, and above all, space advocate, he’s lobbied for a human voyage to Mars for about three and a half decades now, even as the US government has dilly-dallied its way through various questionable exercises in pork-barrel spending. It’s 2025 and human boots haven’t even returned to the Moon yet, let alone touched the Red Planet. Nevertheless, Zubrin soldiers on, energetically helming his own advocacy group, the Mars Society, while publishing a flurry of books promoting his views. For today’s post we will review one of his more recent titles: The Case For Space, released in 2019 by Prometheus Books. Here, Zubrin presents a grand vision of a human future off of Earth, laid out step by step, extending from the Moon to Mars and the starry realms beyond. It’s stirring stuff, meticulously researched and elegantly argued. But does his roadmap hold merit?

Getting off the ground

The first chapter of The Case for Space begins very close to Earth, with a discussion of the costs involved in sending payloads to orbit. Rockets are expensive! Between the 1970s and the early 2000s, the cost per kilogram of payload held steady at about $10,000; if I wanted to launch my beat-up Scion xD, which isn’t exactly a monster truck, it would set me back some $12 million. You’re not colonizing Mars anytime soon with that price tag. To do more than send up the occasional space probe, as NASA has been doing, you need to find a way to bring costs down—and radically.

Here, the author demonstrates a talent for economics that will stay front and center through the rest of this book. With figure after figure, and a whole host of citations, he breaks down exactly why orbital launches are so prohibitively expensive, and what can be done to counteract that. Dramatically reducing the cost of spaceflight is a precondition for everything else discussed in this book, so it makes sense that he starts here.

Reusability is one of the most obvious points for improvement. It would be madness to toss each Boeing 737 into the ocean after its first flight, so we shouldn’t do that with rockets, either. Back when The Case for Space was written, SpaceX had already demonstrated first-stage recovery and reuse with the Falcon 9. There is much discussion of SpaceX’s Starship, then only a concept, which promised reusability and considerable economy of scale. Now, of course, Starship has made nine (highly explosive) test launches, and is well on the way to routine flying. Zubrin’s prediction for its eventual launch-to-orbit price tag? $25 per kilogram. At that rate, I could launch my car for less than I make in a year. Progress!

Zubrin also rails against cost-plus contracting, the traditional model for companies like Boeing and ULA, whereby the government pays the full, self-reported cost of the launch, plus a percentage markup. The perverse incentive is that contractors get paid more if they inflate their costs. In a fixed-price model, meanwhile, the government pays a flat rate and the contractor keeps the difference as profit, encouraging the leanest, most efficient operation possible. This is the way things are done in the private sector. When you pay a mechanic $500 to fix your car, that’s a fixed-price contract.

Zubrin has libertarian political leanings, and that manifests in a strong enthusiasm for free-market solutions. I’m far from a libertarian, myself, but in the case of spaceflight, he has some good ideas. Private ventures have vastly increased the pace and scale of space exploration over the past decade and a half. The traditional industry heavyweights got complacent, lavished with government cash while insulated from competition, so it’s indisputably a good thing that the new challengers, like SpaceX, have lit a fire under their collective rears.

Doing business in space

So, we have our more efficient launch infrastructure, and we can put things in orbit without breaking the bank. Now what? Even if the door to space is opened, people have to want to go there, so the development of a sustainable off-world presence depends on economic incentives. Thus, Zubrin devotes the second chapter of The Case for Space to the commercial uses of Earth orbit.

One possibility he brings up is using rocket boosters for high-speed, around-the-globe passenger flights—anywhere on Earth, in half an hour. Elon Musk has proposed as much as an application for Starship. But frankly, I’m not convinced. A 30-minute trip from Shanghai to London sounds nice, until you factor in the crushing 3-g accelerations along the way. Elderly or otherwise infirm passengers will have trouble. Then there are the security issues around what is essentially an ICBM, but with people in it: both will look the same on a radar screen. One could, hypothetically, camouflage a nuclear first strike beneath routine point-to-point space traffic…

All that being said, there are other potential space industries that seem a lot more promising. Tourism is an obvious one. Zubrin discusses both suborbital sight-seeing trips and longer stays aboard space hotels. He also suggests business parks for research and industry, taking advantage of the unique conditions of weightlessness, something which has been proposed on and off since the days of the Space Shuttle. There’s a passing mention of satellite megaconstellations like Starlink, which were theoretical in 2019 but have become a reality in the years since.

What I found most interesting was Zubrin’s take on space-based solar power—fleets of enormous power stations in geostationary orbit, which would harvest energy from sunlight and beam it via microwave to receiver stations on Earth. They would have the advantage of (almost) always being in direct sunlight; disadvantages include the immense cost of launching them into space, and the absorption by the atmosphere of about half their beamed power on the way down.

Zubrin concludes that such orbiting stations will never be an economical replacement for ground-based power generation. Even with reusable launch systems and mass production, the price of space-based solar electricity would come out around $0.68/kWh1, compared to $0.06/kWh typical for the US energy grid. But that is not to say this technology has no future. What if you’re operating an Antarctic research base, and you don’t have the luxury of a conventional electricity grid? The ability to beam usable electricity on demand to any location on Earth is nothing to sneeze at, and niche customers, if not the general market, could very well provide the necessary demand.

From the Earth to the Moon, and on to Mars

We have seen some business cases for Earth orbit, and the technological means by which they might be realized. What about further afield? The Moon has attracted a lot of attention lately, with countless headline-grabbing probe missions touching down all across its surface, while the US and China are in a race to eventually land people there. Zubrin has much to say about how we might best go about establishing a viable lunar presence. He is critical of the existing plan, under NASA’s Artemis program, which entails a Moon-orbiting “base camp” called the Lunar Orbit Gateway. To give you a sense of just how critical we’re talking about:

“This boondoggle will cost several tens of billions of dollars, at the least, and serve no useful purpose whatsoever. We do not need a lunar orbiting station to go to the Moon. We do not need such a station to go to Mars. We do not need it to go to near-Earth asteroids. We do not need it at all” (Zubrin 71).

What does Zubrin propose as an alternative? Back in the ’90s he made a name for himself promoting Mars Direct, his scheme to send humans to Mars at bargain prices, so it’s fitting that he is also the author of Moon Direct. He describes it at length in a chapter in The Case for Space; you can also read it for yourself in this op-ed in The New Atlantis. Moon Direct would establish a crewed lunar base using only Falcon Heavy and Falcon 9 rockets—three of the former, and two of the latter. Further flights to the base would cost NASA only $250 million a year, a tiny fraction of the agency’s budget. There would be no need for the Space Launch System, or the Gateway space station, or even Starship.

Looking further out, the author explores some ways the Moon could, once developed, become a linchpin for a broad-based Solar System economy. Its poles harbor water ice, for starters. With enough electricity, which would be easily obtained through solar power on the sun-baked, cloudless lunar surface, water can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen—rocket fuel. The Moon also has aluminum, titanium, and silicon embedded throughout its rocks and regolith, offering plentiful building materials for near-Earth space.

The main export of interest to Earth is helium-3. This is an isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron, as opposed to the more common isotope, helium-4, which has two protons and two neutrons. Fusion reactions between helium-3 and deuterium have long been proposed as a clean power source, offering high-density energy production without creating radioactive waste. Helium-3 is extraordinarily rare; while it is more abundant on the Moon than on Earth, thanks to billions of years of deposition by the solar wind, you would have to process 250,000 tons of lunar soil to extract one kilogram of helium-3. Thankfully, the stuff would be more than valuable2 enough to justify the effort. That kilogram, if used in a fusion reactor, would provide more than a hundred million kilowatt-hours of electricity—worth about $6 million.

So that’s the Moon. As for Mars, Robert Zubrin has relatively little to say about it in The Case for Space, which is a surprise coming from the most prolific Mars advocate alive today. Chapter 4, “Mars: Our New World,” is a slim 22 pages, compared to 30 for Chapter 3, “How to Build a Lunar Base,” and 25 for the subsequent chapter on asteroids. Then again, he has written whole books on Mars. No need to belabor the subject here. He briefly goes over a near-future scheme for putting human explorers on the Red Planet; then, colonization, and eventually, terraforming.

Frankly, I’m not convinced by the economic arguments in this chapter. Creating a self-sufficient civilization is hard, especially in an environment several times more hostile than Antarctic. Inevitably, a Mars colony would depend on vast quantities of imports for a very long time, tethering it to the whims of its corporate or government sponsors3 on Earth—who may come to resent having to send resupply shipments every launch window, to colonists who can offer little if anything in return. Zubrin acknowledges this problem. Shipping food or mineral ores to Earth would never be cost-effective; maybe the high deuterium4 content in Martian water ice could make fusion fuel an export commodity, though that’s doubtful, too. Instead, Zubrin argues that the real economic value of a Mars settlement would be intellectual property: patents.

The Martians would inevitably be a resourceful people, his thinking goes. As pioneers on a new planet, carving out a small and fragile bubble of Earthlike conditions in the vastness of a frozen, irradiated, near-airless desert, they would be forced by necessity to develop new technologies, many of which would have applications on Earth. Revenue from patents for these technologies would fund the imports needed to sustain and grow the Mars colony.

Now, I don’t doubt that desperate circumstances breed innovation, but this seems to me like awfully shaky ground on which to base the economic future of millions of people. To my knowledge, there is absolutely no precedent for a resource-hungry colonization scheme funded by intellectual rather than physical exports. Can a few plucky, resource-strapped colonists make discoveries that well-funded terrestrial labs can’t? Would those discoveries be of any value back on Earth? Nobody can say. Any revenues from patents might be a drop in the bucket, compared to the billions of dollars of imports needed just to keep the colonists alive.

The Case for Space tries to tackle the thorny economics of settling Mars, and I give the author a lot of credit for seriously discussing the difficulties involved, instead of brushing them aside. But his proposed solution seems weak to me; the problem is far from being solved.

Asteroids, outer worlds, and beyond

On from Mars, then, to the Asteroid Belt. There is, truly, a ridiculous amount of raw material floating around out there—about a million asteroids have been discovered and tracked so far, ranging from wayward boulders the size of cars to minor planets hundreds of kilometers across. Many of these asteroids are known to contain minerals like gold and platinum, in concentrations equaling or exceeding ores on Earth. So why not put on a headlamp, grab your pickaxe, and go prospecting?

Asteroids represent one of the best near-term avenues for human expansion into space. Even with modest infrastructure, it could be profitable to mine platinum-group metals, refine them, and bring them back to Earth—though as Zubrin notes, there’s just so much of the stuff that large-scale asteroid mining would crash prices fairly quickly. So if you ever wanted to make a solid gold statue of your chosen deity, demon, and/or cult leader, you might soon have the chance to do so, without breaking the bank. This is to say nothing of the implications that an explosion in rare-earth metals could have for computers and electric vehicles…

Zubrin discusses at some length the legal framework that would be needed to make asteroid mining viable. At present, law in space is governed by a set of international treaties signed in the 1960s, which are often vague in their language and do not take into account the possibility of private actors. Arguably, the Outer Space Treaty prohibits the appropriation of outer-space resources. Newer laws in the US, and in Luxembourg (of all countries), have given an explicit green light to asteroid mining efforts, though new regulations have yet to be internationally standardized. Future legal rulings may either spur an off-planet gold rush, or delay it by decades.

One striking idea we see in this book is that of an interplanetary triangular trade. According to Zubrin, a future spacefaring civilization would have three main centers: Earth, Mars, and the Asteroid Belt. The Asteroid Belt would send precious metals to Earth; Mars would supply the Asteroid Belt with food and equipment, thanks to its low gravity and convenient position; Earth, coordinating it all, would send high-tech manufactured goods to Mars. With a sufficiently developed presence in the Asteroid Belt, this might solve the economic problems for Mars, mentioned above. But it also seems possible that a Belt-mining effort would bypass Mars entirely—particularly if it uses robotic craft for its operations, with less need for resupply.

Robert Zubrin devotes only one chapter to the outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. For the most part, these don’t offer particularly good prospects for human habitation. Io and Europa, the innermost of the major Jovian moons, orbit so deep in Jupiter’s radiation belts that colonists would receive lethal doses in a matter of hours. Even on Ganymede, people would have to spend almost all their time indoors and behind shielding. That leaves Callisto as a reasonable destination. Callisto is mostly made of ice, though, and I would be concerned about the availability of metals for construction. And that far out from the Sun, any energy sources would have to be nuclear.

Speaking of nuclear power: like the Moon, the outer planets contain large quantities of helium-3, which could be harvested by atmosphere-skimming craft and then exported to fuel fusion reactors elsewhere in the Solar System. Saturn is the best candidate for this. Jupiter’s gravity well is just too deep for economical mining, and Uranus and Neptune are too far out. Zubrin sketches out a detailed vision of a developed Saturn system, what he calls the “Persian Gulf of the Solar System,” whereby colonists based on Titan would harvest helium-3 from the gas giant’s atmosphere and ship it to hungry customers on Earth, the Moon, and Mars. Titan’s nearby location, large size, and abundance of natural resources (water ice and hydrocarbons, especially) would make it especially suited for the role of an interplanetary Kuwait.

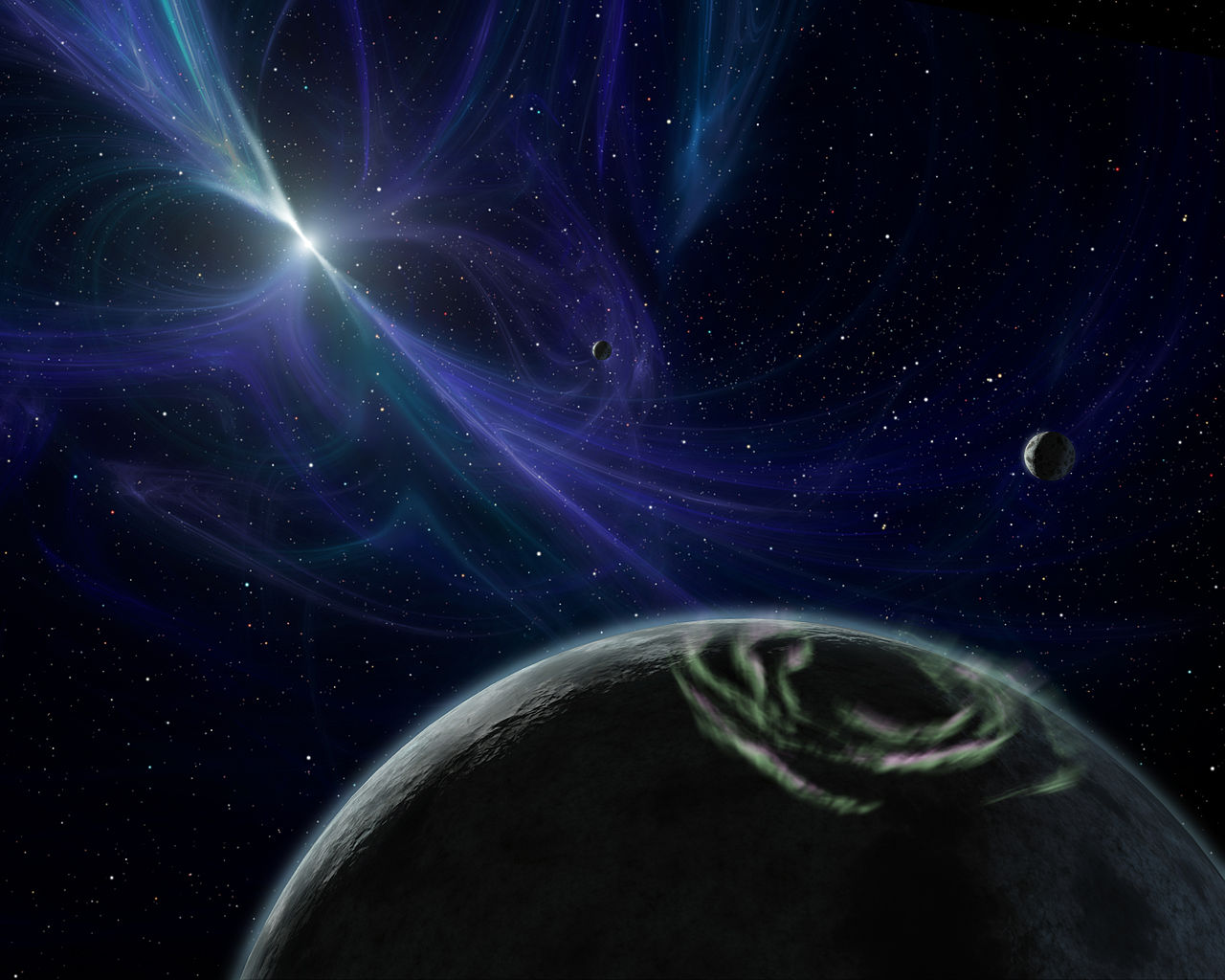

The following chapter delves into interstellar travel. While Zubrin may have focused most of his career on the near-term exploration of Mars, he has no desire for humanity to remain limited to the Solar System. He briefly discusses the magnitude of the challenge—with all but the most fantastical of technologies, any such journey would be measured in decades, if not centuries—and debates some classic solutions for overcoming it: nuclear pulse propulsion, generation ships, antimatter rockets. Most of this material will be familiar to starflight enthusiasts, but it makes for a great primer on the subject.

The author’s preferred starship is a lightweight one, carrying no intrinsic propulsion of its own, which would use a laser-driven sail to accelerate to a fraction of the speed of light, then, decades later, slow down around the target star with a kind of magnetic parachute. As it so happens, I agree that this is the most realistic way to travel interstellar distances. I’ve written about it in a blog post and a short story. Zubrin proposes using such craft to seed extrasolar planets with human and animal embryos, growing outposts of civilization almost from scratch. The specifics of his scheme are… imaginative.

The problem: We’ve sent a shipload of 1,000 frozen human embryos to an Earthlike planet in another star system. But 1,000 embryos does not a colony make. Somehow, they need to be gestated, born, protected, and raised to maturity. What could possibly do all that, while also fitting within the ship’s 300-gram payload?

Possible solution (1): Self-replicating robot nannies. This seems like the obvious answer. But wait—robots need metals, like iron, aluminum, silicon, and lithium, none of which are likely to exist in accessible form on the planet’s surface.

Possible solution (2): What if we had self-replicating robots, but they were made of things like carbon and water? And they might comprise millions or billions of cells, which would serve different functions, and they would grow by consuming organic matter from their environment. Indeed, these “robots” would look suspiciously like life as we know it. Let’s have Zubrin himself explain the idea:

“There are, or were at one time, large, highly complex organisms on Earth, such as octopus, fish, and extinct amphibians, born from milligram-sized eggs. Most of these animals had no parental instruction but had all their required intelligence and necessary behaviors programmed into their genomes. So let us say that we made it our business to engineer a new species of such animals, perhaps resembling large salamanders like the newts in Karel Čapek’s famous novel The War with the Newts, but programed with a set of instinctual behaviors allowing them not only to hatch, grow, survive, and multiply, but to build houses, farms, orchards, industries, incubators, nurseries, and schools suitable for gestating and raising the first generation of humans drawn from the thousands of fertilized eggs contained within the ark” (Zubrin 212).

And there you have it! Interstellar colonization via giant salamanders. I, for one, welcome our new amphibian overlords.

Why bother?

Some this book’s most intriguing sections, in my view, have to do with philosophy rather than engineering. Robert Zubrin clearly has a grasp of the humanities alongside his technical background. Part I of The Case for Space, “HOW WE CAN,” concerns the engineering and economic challenges of space colonization, as detailed above; Part II, “WHY WE MUST,” goes into the political, moral, and philosophical. Zubrin subdivides this section into five chapters, each corresponding to one justification for human expansion into space:

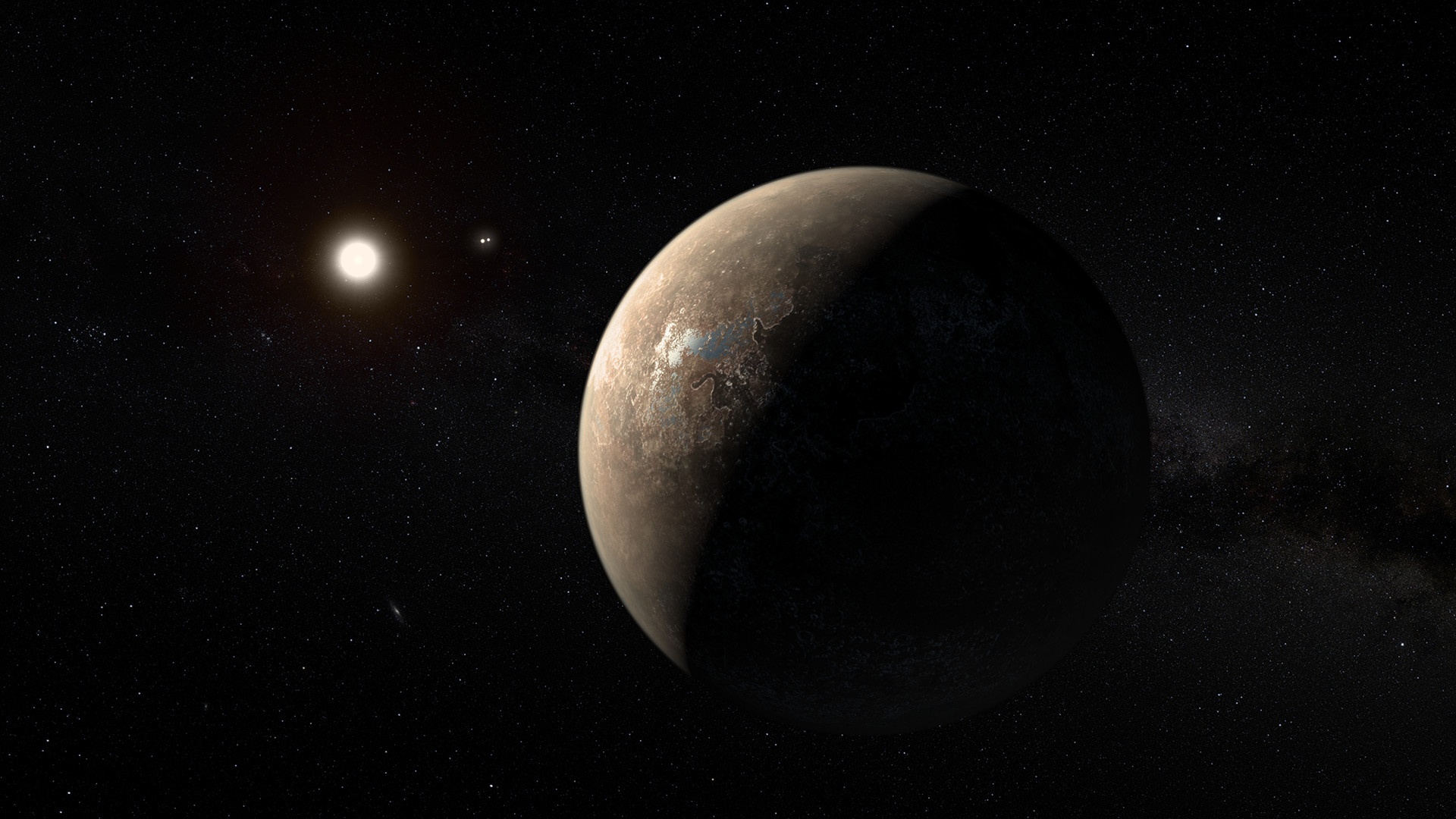

- “For the Knowledge”: We should go into space to unlock the secrets of the universe. Are there other Earthlike worlds out there? What about life? Intelligent civilizations? What if our understanding of physics, now, is scarcely more complete than it was in Galileo’s time, and there are profound scientific truths yet to discover? Between space-based observatories and deep-space expeditions, we will make far more progress on these questions by going out there and looking, as opposed to staying at home.

- “For the Challenge”: Current human civilization is at risk of stagnation, in Zubrin’s view. He reiterates the Frontier Thesis of Frederick Jackson Turner: that America owes its dynamism, creativity, and unique world-historical character to its expansion across the western frontier. The closing of the frontier—in this case the blanketing of Earth by an inescapable, interconnected, world-encompassing civilization—threatens to extinguish that potential, leading to economic as well as cultural decline. What we need, then, is a new frontier: space. To conquer space will energize humanity in pursuit of a constructive goal, and create the potential for countless new, diverse, perhaps greatly improved offshoots of terrestrial civilization.

- “For Our Survival”: Earth isn’t going to be around forever. It also isn’t invulnerable. Our place in the Solar System puts us in the middle of a cosmic shooting gallery, and we need a spacefaring civilization if we are to survive it—because only a spacefaring civilization can detect, approach, and redirect the near-Earth asteroids which periodically threaten to hit our home planet. Had they had such a capability, the dinosaurs might have averted their own extinction. Hopefully humans will prove more successful than they did.

- “For Our Freedom”: The perception of limited resources on Earth will lead to totalitarianism, warfare, and perhaps genocide. Mainstream environmentalism is an anti-human, anti-progress ideology. Space, however, offers a more humane and bountiful future, as well as a frontier so vast that no tyrant could ever control a fraction of it. Lasting human freedom lies in the stars.

- “For the Future”: A human civilization encompassing the Solar System would be capable of things we can scarcely imagine today. One encompassing the galaxy, even more so. The growth of humanity into the universe opens up possibilities so grand, so beautiful, it would be an act of madness to turn away from them.

As a general rule, I agree with the arguments in this book. I, like the author, am a supporter of space colonization, if quite not such an idealistic one. Should we look out into the cosmos for scientific reasons, relentlessly pursuing knowledge for its own sake? Of course. Would space colonization be a worthy focus of humanity’s creative efforts and innate drive? Yes—though global crusades against climate change and poverty would be worthier, still.

While I grant that challenge is a good and healthy thing, I disagree with Zubrin’s invocation of the Frontier Thesis. It’s extremely controversial among modern historians; for one thing, it lionizes the violent expansion of Euro-American settlers, who displaced and often massacred indigenous peoples in the process of conquering the continent. Holding up such an event as a model for the colonization of space may not go over well in some quarters, and there are better historical metaphors out there.

I also challenge the author’s characterization of environmentalism as anti-human. It’s deeply undeserved. Sure, you get the extreme types who think everything since the Stone Age was a mistake, and are positively rooting for the collapse of civilization, but we’re not all like that. You can care about climate change without viewing humanity as a cancer to be eradicated from the Earth. You can also support the colonization of Mars without downplaying the catastrophic impacts we’re currently having on our home planet. There are nuances to these things!

Those are my main gripes. But again, Zubrin mostly hits the mark. His vision of a boundless human future, of dynamic new societies sprouting up across the Solar System and beyond, is an exciting one.

General thoughts

The Case for Space is an optimistic book. It’s hard not to get caught up in Zubrin’s vision, laying out a roadmap for an exceptionally abundant future—and indeed, it’s a good antidote to the pessimism that’s all the rage these days. Do I think large-scale space colonization is quite as realistic as the author claims? Not necessarily. The settlement of Mars, in particular, strikes me as more difficult and dangerous than he makes it out to be. We just don’t know how a small, self-contained ecosystem, populated by humans, would hold up in a nigh-airless wasteland, without any existing biosphere to draw from, under gravity much lighter than Earth’s. It might work just fine, mind you! But we just don’t know. Rushing thousands of people there with no backup plan may not be the right move.

The writing on display here is well-written and persuasive, even where it ventures into the far-fetched (see: salamanders, above). Those with no technical background at all may have trouble following all the equations, tables, and chemical formulas, but Zubrin doesn’t leave the reader completely in the dust. The important points are pretty clearly explained, without too much assumption of prior knowledge.

For lifelong space enthusiasts, The Case for Space offers plenty of intellectual meat to chew on, and those less familiar with the subject will learn a lot about the past, present, and future of space travel. This book would make great reading for either group. It succeeds, too, as a piece of political advocacy: Robert Zubrin puts forward clear, cogent arguments for investment in human spaceflight, which may well persuade those who are on the fence, or further encourage those who already agree with the author. I, myself, am feeling pretty jazzed-up after reading it. Hopefully, you will, too—the cosmos awaits.

Rating: 9/10. Heartily recommended!

Thanks for reading this one, my friends. It’s good to be back, after the long hiatus. My plan is to freestyle for a bit, until I work out a consistent schedule again, so I’ll see y’all the next time I see you; until then, take care!

- Kilowatt-hour. Power, measured in watts, does not refer to an amount of energy, but the rate at which it is delivered; a kilowatt-hour, then, is the total quantity of energy delivered by one kilowatt of power in one hour. ↩︎

- Assuming we can achieve net-positive fusion power, which is no small assumption. Until then, the market value of helium-3 is more or less zero. ↩︎

- This is one of many factors that doomed the ill-fated Mars One scheme, back in the 2010s: committing yourself to a Mars colony, requiring regular and expensive interplanetary shipments for at least several decades, is not a winning business move. ↩︎

- A rare isotope of hydrogen with a proton and a neutron, instead of just a proton. It’s a component of some lower-energy (but more easily achievable) fusion reactions. ↩︎

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply