Very early on, my family instilled in me a love of coffee table books: hefty, hardcover volumes, large enough to double as paperweights or even footstools1, bedecked with photographs and artwork from front to back. Instead of reading straight through, you could open one to whatever page you fancied. They covered all sorts of topics, from sea life to geology, from medieval Europe to ocean liners. My favorites, though, were about space—the science, the history, the fantastic vehicles with which men have plumbed the unknown. More than two decades later, I still have a few of these sitting on my shelf.

Today’s post is all about the big, the bold, and the old. I’ll show off two volumes I’ve had with me since childhood, and two I’ve chanced across more recently. All of them are absolutely popping with imagination. They might be outdated, missing more recent space missions or containing facts later proved erroneous, but they are no less marvelous for it—between their covers lie time capsules from a wonderfully imaginative past. Let’s dive in.

The History of Space Vehicles (Tim Furniss, 2001)

Our first stop is the book I’ve had the longest, which in correspondingly dire condition. You could breathe on this thing and the binding would come off. The History of Space Vehicles is, as my dad used to say, “well loved”; I spent many nights curled up in bed with it, marveling at the illustrations before I had even learned to read, and at a later age, it proved surprisingly helpful for school projects. What we have here is an illustrated survey of the entire history of spaceflight, shallow in depth but impressive in scope.

The first chapter hits the ground running with a discussion of Robert Goddard, the V-2 rocket, and the postwar missile development that led directly into the Space Race. Everything up to Sputnik 1 fits in a mere 25 pages, and the text here isn’t exactly dense. Chapter Two, “The First Five Years,” details the early satellite launches; Chapter Three, “The First Manned Space Vehicles,” absolutely sprints through Vostok, Mercury, Gemini, and Voskhod; and after that, we’re already on the lunar landings!

Later chapters cover the Space Shuttle, the commercial launch industry, and interplanetary probes. Mind you, this hit the printing press all the way back in 2001. A non-exhaustive list of things that hadn’t happened yet:

- Most of the International Space Station.

- The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

- The Chinese manned space program (though it does get a mention near the end).

- Cassini‘s arrival at Saturn, and the landing of Huygens on Titan.

- Absolutely anything to do with SpaceX.

- Three whole eras of US space policy: the Constellation Program under George W. Bush, the current Artemis Program of Trump and Biden, and whatever Obama was trying to do.

A lot has happened in this century! But The History of Space Vehicles provides a glimpse into a markedly different time, when the Space Shuttle was still flying every couple of months, crusty Old Space contractors had a monopoly on launches, and the competition of the Cold War had given way to the big “now what?” of the neoliberal world order.

That’s the substance. As for style, there’s a lot to like here. The full-color illustrations are gorgeous, clearly drawn with a lot of love, and integrating fun factoids with detailed cutaways. The text (though riddled with typos) is a fast, light treatment of the subject matter; hardcore space buffs will still find plenty to enjoy here, as a survey and summary, even if brand-new knowledge isn’t in the cards.

Perhaps the most interesting chapter is the last one: “Space Vehicles of the Future.” We see how 2001 saw the 2010s and beyond. There are features on the Chinese Shenzhou capsule, which actually flew, and Boeing’s single-stage-to-orbit VentureStar, which died an inglorious death just months after this book was published. Also present are far-fetched ideas like the Roton helicopter (!) launch vehicle and a piggybacking two-stage spaceplane. Possible Mars landings and an ice-drilling submarine on Europa get their due, as well.

Tim Furniss’s predictions for the future are surprisingly gloomy. The turn of the millennium was a time of constrained budgets for NASA, without a long-range US space policy of any kind. In the author’s own words: “Media expectations and corporate oversell have created an atmosphere of doubt and uncertainty around the value of space travel and exploration. To many, the Apollo programme, and the successful landing of men on the Moon [sic] was the culmination of man’s efforts in exploring space.” Say what you will about launch delays and other frustrations these days, but there have certainly been worse times for spaceflight.

The History of Space Vehicles is absolutely worth checking out, if you’re lucky enough to find a copy. I wouldn’t part with mine for any price—and it’s pretty beaten-up, anyway—but you may be able to snag a used one off Amazon.

The Space Atlas (Heather Cooper and Nigel Henbest, 1992)

Our next feature focuses less on vehicles, and more on science. The Space Atlas, another childhood favorite, is a slim but colorful volume offering a brief tour of the universe to middle-grade readers. There are overviews of orbital launches and the Apollo missions; maps of the near and far sides of the Moon; portraits of each of the planets, including Pluto, as well as their more notable satellites; and, looking further, explorations from nearby stars out to intergalactic space. Awfully ambitious for 63 pages of hand-drawn artwork!

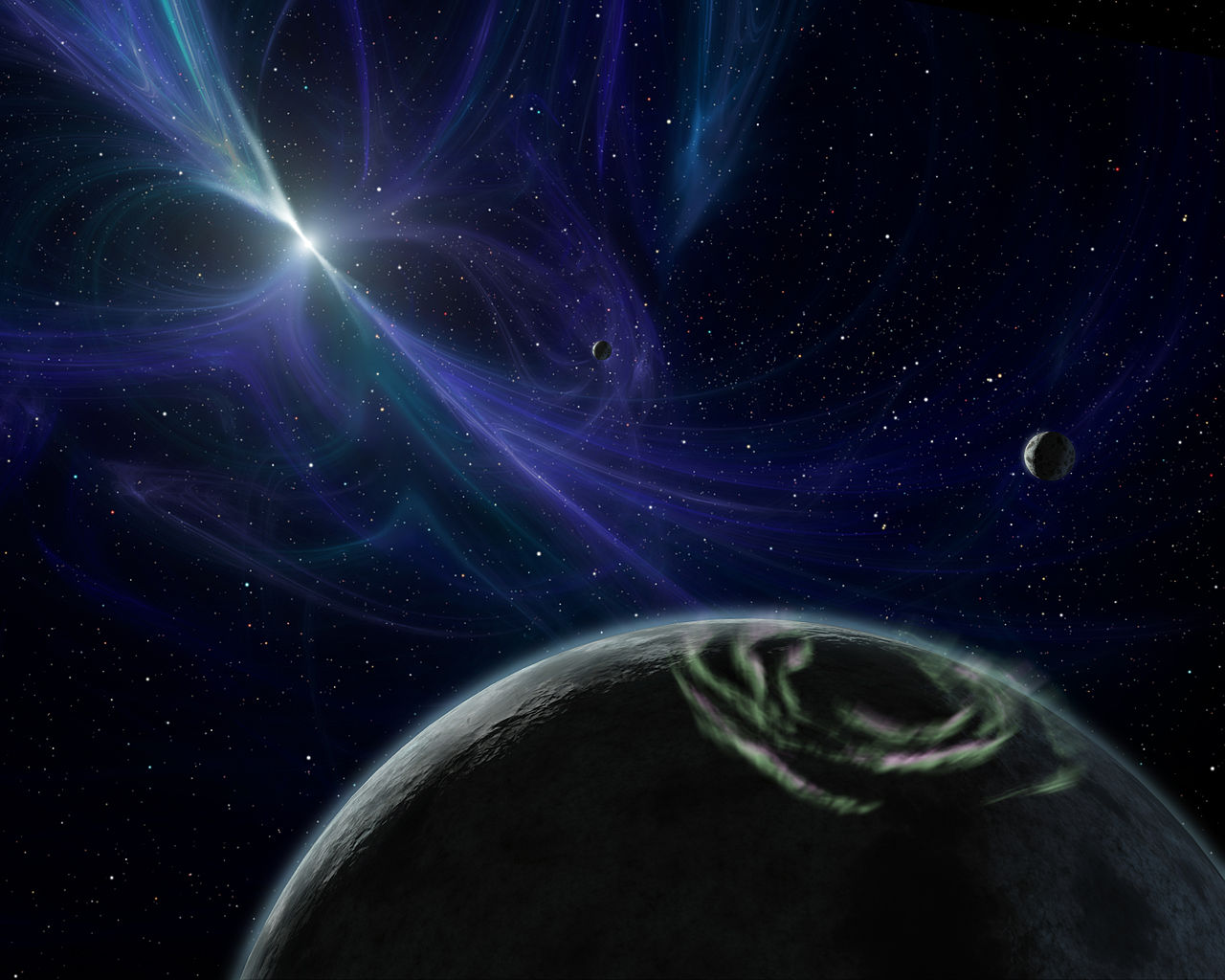

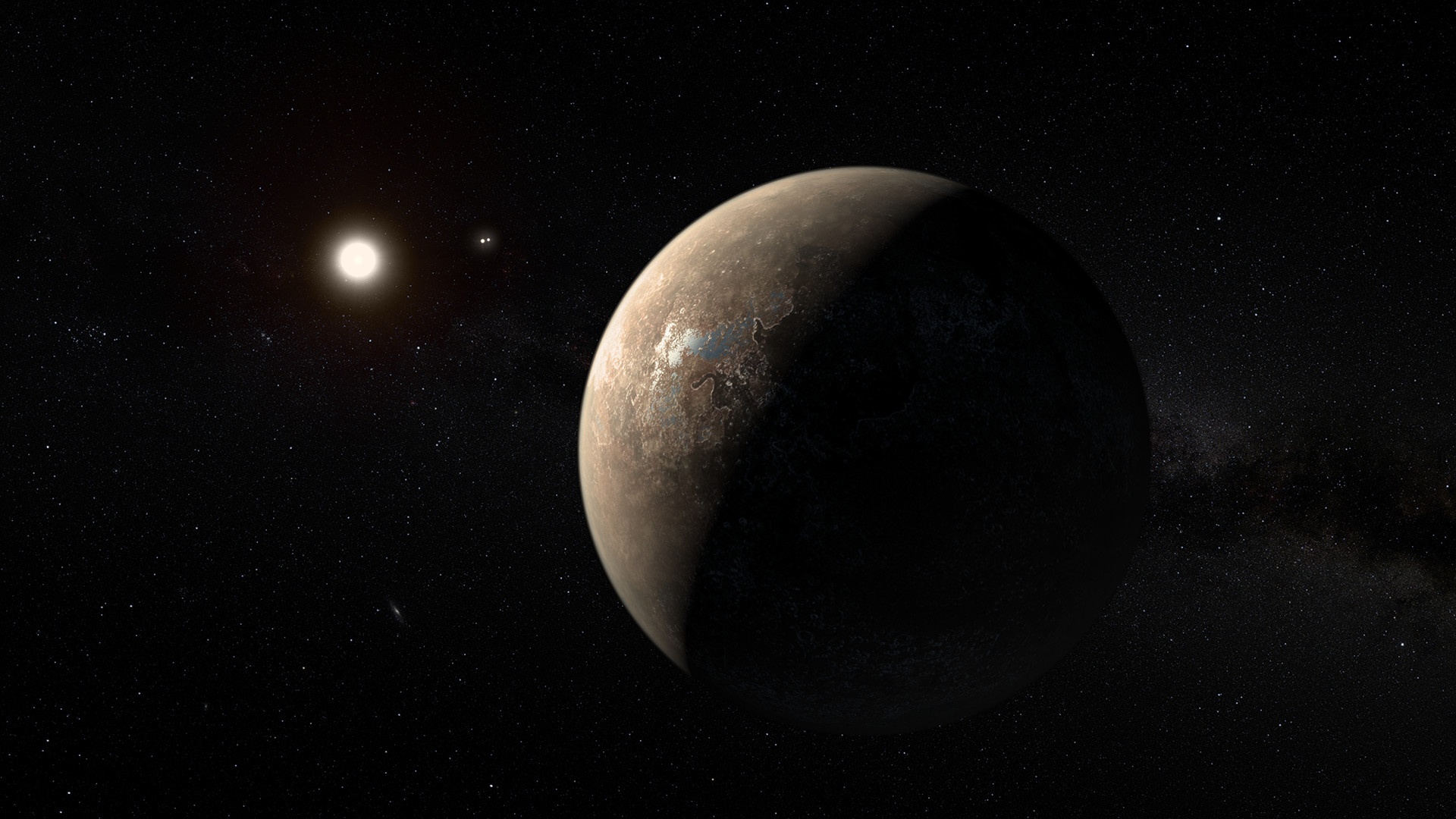

Probe missions and planetary science are integrated seamlessly together here. I’ve got to hand it to whoever did the page layout—they had a lot to juggle, and still put out something polished and informative, but still visually busy enough to appease my maximalist taste. The artwork itself is excellent, too. We see labeled, lavishly detailed views of eight planets; at the time of writing, probes had only ventured as far as Neptune, so the depiction of Pluto (still a planet) is conjectural. Ceres also gets the speculative treatment. While launch vehicles and near-Earth space missions only take up a few pages, there are some striking images of rockets in flight. Looking further out, to the stellar and galactic realms, we see some gorgeous illustrations of nebulas, black holes, and star formation.

Earlier, we saw that The History of Space Vehicles is out of date only because its timeline stops in 2001. With The Space Atlas, by contrast, we’re dealing with scientific ideas that were later overturned. That’s not to imply any fault on the part of the writers or artists—science is all about correcting itself—but it does make for some illuminating reading. For example, the authors speculate about a pair of large exoplanets orbiting Barnard’s Star; this is presumably based on the work of Peter van der Kamp, who claimed to have discovered such planets in the 1960s, after observing a wobble in its position in the sky. We now know that van der Kamp’s observations were actually measurement error caused by cleaning his telescope lenses.

There is also a brief section on Planet X2, an icy super-Earth lurking in the very outermost reaches of the Solar System, which was supposed to resolve certain irregularities in the orbit of Uranus that could not be explained by Neptune or Pluto. This possibility opened up in 1978, when Pluto turned out to be much less massive than originally thought; it was disproved in 1992, the year this book was published, when a second look at Voyager 2 data revised Neptune’s mass upwards, and removed the need for a Planet X to fill in the gaps. Nevertheless, the page on Pluto includes a splendid drawing of Planet X, because this book’s authors just barely missed the memo.

So that’s The Space Atlas. I absolutely recommend this one, if you ever come across a copy for yourself. Sadly, they don’t seem to make books like it anymore—utterly earnest, filled with hand-drawn illustrations from cover to cover, with no computer-generated imagery in sight. Perhaps there should be a return to the old ways? While we’re at it, I suppose we could trade in our smartphones for carrier pigeons.

Quest for Space (F. Carassa, L. Broglio, C. Bongiorno, et al., 1985)

Of the four works I’ll be looking at today, this one is… quirkiest. I came across it two years ago, tucked away among the shelves of Powell’s Books3, offered for the shockingly low price of $8.50. I couldn’t resist picking it up. Looking online you will find few traces that it ever existed; the Goodreads page has one rating and zero reviews. A glance at the inside cover will reveal that it was first published in 1985 in Italy, by authors representing a spectrum of engineering professors, journalists, and astronomers. Crescent Books released the English translation in 1987. Like The History of Space Vehicles, it presents a comprehensive overview of space vehicles and missions, except in much greater detail. Much greater. We’re talking walls of text:

If you ever wanted to know the minutiae of every space mission ever (up to 1987), you have it! Thankfully, the full-color illustrations do a lot to break up the columns and paragraphs. And there’s no shortage of illustrations—the artists, Amedeo Gigli, Egidio Imperi, and Pierluigi Pinto, did a very good job populating this book with some visual splash. You’ll note that I’ve already mined it for diagrams of the Vostok capsule and a Soviet lunar probe. The double-page artwork, interspersed throughout, can downright breathtaking.

The authors also added several of their own essays, in between chapters on launch vehicles, satellites, interplanetary probes, and so on. Titles include “The Utilization of the Space Environment” and “Technology and Safety in the Journey Through Space.” I have to admit, I still haven’t read most of these—the dodgy translation job certainly doesn’t help things. They’re mostly fluff, rambling on without much in the way of substantive claims. I would know something about that from my time as a humanities student…

Most of my gripes with this volume have to do with the writing, come to think of it. While Quest for Space contains a wealth of information, its usefulness is sometimes undermined by confused, ambiguous wording. Even passages that read clearly have a certain stylistic awkwardness about them. But on the whole? This is a fantastic resource. It’s tons of fun just flipping through, reading technical details about this or that space mission, and the illustrations add tremendously to the atmosphere—I’m truly grateful to have stumbled across it one rainy afternoon in Powell’s.

National Geographic Picture Atlas of Our Universe (Roy A. Gallant, 1980)

This, here, was another lucky find—and perhaps the most gorgeous of the books I’m reviewing today. I encountered it two years ago in an antique shop on the Oregon coast. Not even one that specialized in books, as it happened. The cover just popped out at me from a shelf full of knick-knacks, and there was no doubt, when I realized what I’d found, that I would walk out of there with that book in my hands.

Like The Space Atlas, above, Our Universe has little to say about space missions and launch vehicles. On the axis of engineering to science, it is firmly in the science camp. And what a trip it will take you on! Though there’s a bias towards the Solar System, it covers the whole grand sweep of the cosmos—from Earth and the Moon through the neighboring worlds, and out to the stars, other galaxies, and the prospect of alien life. Each planet gets a section of basic details (orbit, temperature, atmosphere, and so on), followed by a more in-depth discussion. The text gives you a great sense for what was known back in 1980. Keep in mind, this was before Voyager 2 had flown by Uranus and Neptune, and long before any rovers landed on Mars. The planets were rather more mysterious than they are today.

One of the most impressive things on display here is the sense of atmosphere—the feeling that you’re being transported somewhere else, far away from your mundane, everyday surroundings. Part of that effect comes from the striking black backgrounds of many pages. Part of it is the dramatic, immersive artwork, showing exotic vistas and strange worlds hurtling through space. I reckon this book inflamed the imaginations of a great many kids back in the 1980s. Sadly, I would be classified as a “young whippersnapper,” and I am rather late to the party.

Our Universe can be charmingly whimsical, too. For every planet, there’s an illustration of the corresponding Roman god: Venus as a beautiful, graceful woman; Jupiter, resplendent with lightning bolt in hand; Mars, wearing his grim panoply of war; and even Gaia, the mother goddess of Earth. Another section presents a zoo of alien creatures, specially tailored to various environments in the Solar System. Some are rather silly. These are not meant as serious speculation—the authors did not believe there actually might be life on the surface of Venus—but as illustrations of how profoundly different the other planets are from the world we know. We’re not in Kansas anymore!

All the books I’ve spotlighted today are beloved parts of my shelf. But this one, in particular, has magic to it. The pages absolutely drip with wonder, with curiosity, with the joy of knowledge for its own sake. We in the 2020s are far too jaded about things, and could stand to rediscover such 1980s earnestness. I’d love for hand-drawn illustrations to make a comeback, too.

That’s all for today, folks. I hope you enjoyed this little tour of my collection. With a little luck, I might have inspired you to hit up a used bookstore, and try to find an old space book for yourself. I will see you all next Sunday!

- It’s possible that instead of a nightstand, I just have a stack of oversized books beside my bed. But I admit nothing. ↩︎

- Distinct from Planet 9, proposed more recently to explain the orbits of certain trans-Neptunian objects. ↩︎

- Arguably the best thing about Portland, Oregon, and there are a lot of great things about Portland, Oregon. ↩︎

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply