Buckle up, everyone—today I’m unleashing another short story on the world. This piece will join “The Return,” “The Devil in the Archives,” and “Selected Communications of the Zygaran High Command” as complete, short-form fiction available for free on my website, and trust me, I have plans for a lot more to come. Read on for a hard-sci-fi tale of a legacy passed on through generations…

Seven Years

The fate of the interstellar project remains in doubt. Despite official authorization by Congress—itself only secured by decades of grueling advocacy and more than a few under-the-table deals—the road ahead is filled with any number of perils, political and technical, which might keep the mighty dream earthbound. Minerva soldiers on, regardless.

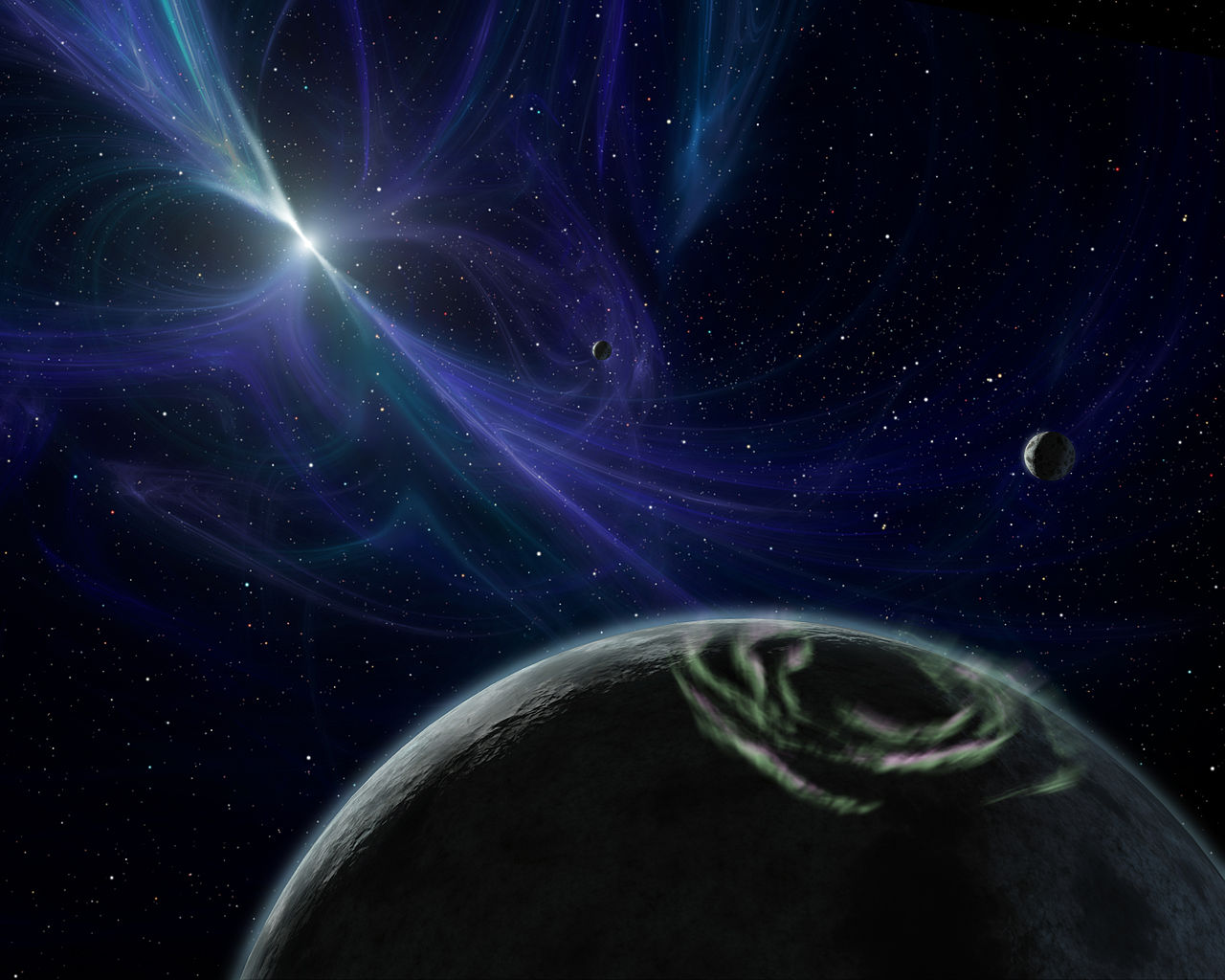

She keeps a picture of the star Proxima Centauri taped up on her office wall, next to photos of her husband and their three-year-old son. She’s in that office up to ten hours a day, five or six days a week, and the inspiring image helps pull her through what is often uninspiring work. This job demands the full strength of her talents; she is head of a team designing a miniaturized camera casing—a mission-critical subsystem of a mission-critical component, which in turn will go into the most complex spacecraft ever built. Everything on the probe must be designed, tested, and refined, meticulously and endlessly, demanding absolute perfection over a mission lasting several decades. Nothing can be allowed to fail.

Minerva is typically wiped out by the time she gets out of the office, which can be very late in the evening. She only just has energy to drive home on the freeway, pull up to her condo, grab dinner from the fridge, and exchange a few words with her husband.

If her son is still up, she’ll read him a bedtime story. It takes effort she can barely muster, but she can’t deny that she looks forward to sitting on the side of his bed each night, turning pages under the glow of the reading lamp, watching a wide-eyed, energetic little boy transform into an angel at rest.

“And then the little red fish knew he’d made it home,” she reads, turning the page. “He was with his family again. They got together and threw a big party…”

She notices that his eyes are closed. He rests on one side, his arms wrapped around his inseparable stuffed dragon, a few curls of black hair closing on an olive forehead. Part of her wishes he could have stayed up longer; this was the only time she’d gotten to see him today, and he’d said all of ten words before falling asleep.

“Sweet dreams, honey.” She leans over to give him a kiss on the forehead. Then, taking care not to shake the bed too much, she gets up, turns off the lamp, and takes soft footsteps towards the door. Hopefully she’ll get more reading in tomorrow.

Five Years

The funding wars seem to be over, for now. The new administration has finally reaffirmed its support, after congressional grumbling, pressure from the scientific community, and lobbying by some of the larger, more powerful contractors. That is not to say that no harm was done. The budget will be lower, from here on out, and to make up that shortfall the project leadership has decided to scrap the second of two orbital laser batteries, which are to accelerate the probe up to a fraction of lightspeed. All resources will instead go to finishing the first battery, under construction in lunar orbit.

Minerva knows the consequences of this. Halving the laser power means halving the thrust on the light sail, and by extension, the ship’s peak velocity in interstellar space. It will now take sixty years to reach Proxima, not thirty. She is unlikely to live to see the results, as she had hoped.

Her dreams are for another lifetime. But her work does not cease, and there are always more meetings to attend, more decisions to make—so Minerva negotiates an uneasy truce with the new reality.

Two Years

Minerva has the singular privilege of peering through the assembly-room window and seeing the probe sitting there on its platform, attended by a swarm of white-garbed technicians, very nearly in its final shape. The greatest undertaking in history is a metal cylinder ten meters long. Some of the metal gleams like silver, while other surfaces have more of a brassy finish. Up front is the bay for the lander, followed by the computer core and sensor bay—the future home of her camera casing!—followed in turn by the mag-brake housing, the xenon tank, the miniaturized fission reactor, and finally the electric propulsion system. The whole thing fits within the size of a schoolbus, and will mass eleven tons when fueled. It’s feather-light, as far as starships go.

There are some things still missing. Next to the ion engine are attachment points for microfiber tethers, which will connect the probe to a light sail over sixteen kilometers across; on the front, there will be a multi-layer shield, to break up stray debris as the probe hurtles through interstellar space; and on the side of the xenon tank, an American flag has yet to be painted. Fundamentally, though, this is what it will look like. This craft, which Minerva can see with her own two eyes, will one day bathe in the light of an alien sun.

Thirteen Months

With a stroke of her pen, Minerva certifies the last integration test. This is it—her team has finished the component on which she spent a decade of her life, and it now will remain in the probe, unmodified, through launch and beyond. While she will continue to advise and monitor, the most critical task is done. She wonders if this is what it will feel like, ten years from now, when her son graduates high school.

She takes the team out for dinner. Ten of them, at least, the senior design leads and a few others. They’re not normally a festive bunch, perhaps with the exception of Frederico, but as they all sit together around a long table, sipping beer and talking about the lives they’ve neglected for so long, the years of anxiety and tedium seem far away.

Angela reveals she’s already got a new job lined up, working on one of the West-Coast desalination projects. Rob, meanwhile, is retiring to spend time with his grandkids—this is a fitting capstone for his career, and family comes first, after all. Frederico explains the probe’s mission to a curious bystander; he gives a pretty good show, putting together a kind of crude model with a salt shaker and a dinner plate, though the restaurant staff are not quite so impressed.

She’ll miss working with these people.

Nine Months

The probe is sterilized prior to launch. Immersion in hot plasma does the trick, seeping through every nook and cranny to fry any living things that might have stowed away. Bacteria are hardy lifeforms—hardy enough, perhaps, for a few spores to survive six decades in interstellar space—and every precaution must be taken to wipe them out, lest they contaminate a potentially habitable world.

One Month

With twenty-eight days to go until the main event—the boost phase—a rocket shuttle carries the probe off of Earth, as it would any other payload. Eleven tons is nothing special in an era when humans mine the Moon for water and build outposts on Mars. The probe enters space unscathed, soaring three hundred kilometers above Atlantic cloudtops.

Instrument tests prove successful. All systems check out. The go-ahead is granted, and a space tug descends from a higher orbit, inching towards the probe in a delicate ballet. The two ships spiral towards each other, while the Earth spins beneath them.

Once the connection made, it is time for the tug to fire its main thrusters, and the pair embark on an eleven-day course beyond the Moon.

Fifteen Days

The final step, before departure, is to mate the probe with its laser sail. This is an exceedingly careful process. Upon arrival at the L2 Lagrange point—a kind of gravitational eddy, about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, where the Earth’s pull and the Sun’s cancel each other out—the automated tug detaches, while another ship, piloted by humans and carrying the packed-up laser sail, flies out from a station at the lunar south pole.

The sail is sixteen kilometers wide. Unfolding it takes two days, and the final product is a vast, mirrorlike disk, a hundred times thinner than a sheet of paper, dwarfing the little craft that will attach to it. It takes another day for the astronauts to carefully run tethers between the sail and the probe: a kind of rigging, stringing together the spacefaring equivalent of a clipper ship.

Three Days

Minerva has been invited to the program headquarters, there to watch the probe’s departure alongside various project leads, administrators, and other notables. Rumor has it that the president will make an appearance, too. She leaves her husband at home with ten-year-old Matthew.

“Be sure to watch the livestream, OK?” she tells her son, moments before heading out the door. “It’s something you’ll remember for the rest of your life.”

“OK, Mom,” Matthew says. He fiddles with his phone, eager to return to it.

“All right. I’ll be back in a week.” She leans over and kisses him on the forehead—though he’s starting to get too tall for that. “Love you.”

She hurries down the driveway, and her husband closes the door behind her.

Zero

All things appear normal. At the appointed time, Mission Control orders the laser station, orbiting the Moon, to commence the acceleration process.

This station is the key piece of infrastructure underpinning the entire mission. It is a facility massing three thousand tons, assembled from lunar materials at significant expense, and its photovoltaic arrays receive beamed energy from a constellation of hundreds of power-sats, which have been diverted from their typical duties to support this once-in-a-lifetime endeavor.

A single photon in this beam takes four seconds to streak through space to the laser sail, millions of kilometers away. It takes only an instant to bounce off the sail’s reflective surface and shoot back more or less the way it came. In the process, it exerts an undetectably small push on the sail. Scale this up enough—1.3 terawatts’ worth of photons, as much energy as a wealthy country’s entire power grid—and that sail will become more responsive. The probe begins to pick up speed, at about half an Earth gravity.

Minerva witnesses this from the viewing gallery of Mission Control. One of the big screens up front carries a host of figures, from power output to orbital velocity to distance traveled, and another shows a live diagram of the probe’s position, moving away from Earth at a stately pace. There isn’t much to look at, otherwise; none of the onboard cameras are active during this phase, and a telescope view of the sail, taken from a satellite nearer to home, shows only the blinding glare of reflected laser light.

The gallery is crowded. As expected, all the upper echelons of the interstellar program came out to see this, so many pressed suits and grey heads of hair, though the president did not end up making an appearance.

Some attendees bite their nails, or tap their feet. They murmur quietly amongst themselves. They cannot be blamed for this—anxiety seems like the correct response, when a 1.3-terawatt laser is firing directly at their life’s work.

After a few minutes, though, Mission Control reports that the sail is working beautifully. The probe itself is unharmed, shielded by its own small mirror. It is not building up any significant waste heat. All readings indicate that it is in stable condition, picking up speed on its way to Proxima Centauri. Champagne corks pop around the viewing gallery. Minerva lets out a long, deep sigh, surprised to learn she had even been holding in her breath.

Four Hours

Minerva calls her husband from the hotel room. She sits near the foot of her bed, the contents of an open suitcase sprawled beside her.

“Hi, hon. Did you see it?”

“Yeah! Congratulations. I know this is a big moment for you.”

“What did Matthew think?”

“He didn’t seem all that interested. Mostly just played around on his phone.”

“What? I thought I told you to make sure he watched!”

“Minerva, the kid’s ten. He’ll appreciate it when he’s older.”

She’s supposes he will—though that doesn’t keep her from feeling faintly wounded.

Seventeen Hours

By now, the probe is hurtling away from Earth and the Sun at three hundred kilometers per second—a breakneck pace, in interplanetary terms, but nowhere near adequate for interstellar travel. At this velocity it would still take thousands of years to reach Proxima Centauri. But the laser continues to fire, and the sail picks up ever more speed.

Thirteen Days

The probe has passed beyond the orbit of Neptune, thirty times the distance between Earth and the Sun. During the last century, Voyager 2 took twelve years to get this far, and that was with several gravitational slingshots along the way.

Fifty Days

The probe has now reached its cruising velocity of seven percent the speed of light—fast enough to create relativistic effect, though not severe ones. When it arrives at Proxima Centauri, its internal clock will lag behind Earth by fifty-four days.

The sail has served its purpose. Explosive bolts cut the tethers between it and the probe, all while the laser is still firing—as a result, the sail flies ahead even faster, no longer weighed down by its payload. Slightly tilting the sail creates a small lateral acceleration, pushing it off to the side and out of the probe’s path. After another few minutes, the laser cuts out, and the probe and its sail are left to coast.

During development, there was some concern about discarding the spent laser sail. Some worried that it could become an unintentional weapon, hurtling through the universe until it hit an unsuspecting civilization with the kinetic equivalent of several hundred nuclear bombs. Further investigation revealed such fears to be largely unfounded; the odds of the light sail impacting any planet, let alone an inhabited one, are vanishingly small, and the current understanding is that it will fly through interstellar space, undergoing gradual erosion by particle collisions, until whatever is left leaves the galaxy about forty thousand years from now.

Fifty-Five Days

In preparation for the longest stretch of its journey, during which it will be bombarded with space dust, the probe pivots so that its particle shield—which doubled as a mirror during the boost phase, protecting the ship from vaporization by the laser beam—now faces forward. As empty as space may be, any collision is dangerous at 0.07 c. Even a micrometer-sized speck can strike with the force of a hand grenade. The particle shield, comprising three plates spaced at intervals in front of the ship, will disperse any such impacts before they can endanger the mission.

Eighty Days

The probe’s systems power down for the long flight out. It will be in hibernation most of the time, save for a few intervals in which it will wake up to run system diagnostics and verify its position against background stars. It will have to do all this without help from the homeworld; Earth is now too far away for anything but a high-power radio antenna to bridge the gap, and such an antenna can only be deployed when it has safely reached its destination, at which point the time-lag will be more than four years each way.

One Year

Minerva has spent the past year wrapping up the interstellar project—which means reports and debriefs, meetings with various higher-ups, the relocation of unused equipment. Now, though, it is time to move on. The office is closing, and its employees are to be scattered to the four winds.

It does sting a bit. The invisible hand has weighed her value to the shareholders, and found her lacking. She’ll collect her severance pay, make sure her resume is in order, and venture back out onto an uncertain job market.

She knows there will be no more missions like this one, at least not for a long time. Facing a financial crisis, and an energy crisis, and the inundation of several states by a monster hurricane, the government is unwilling to fund any more interstellar expeditions—particularly when the payoff is many decades in the future, beyond the lifespan of nearly anyone alive today. There are more immediate problems to deal with than the exploration of the cosmos. The laser station in lunar orbit will be pressed into military service, over vehement objections from the space program, and pointed at the hungrier, more disciplined powers eager to claim space for themselves. The probe’s extensive technical documentation will go into secure storage in a warehouse somewhere, there to collect dust for indeterminate years to come.

She doesn’t lose all hope. Long after her time, she’s sure there will be more flights to the stars. She reminds herself that after the Apollo program, it took humans sixty years to send anyone back to the Moon—and look where they are now.

Ten Years

Matthew is all grown up. He has no technical inclinations, unlike his mother, and his dreams are much closer to Earth: a house, and a family of his own. Seeking a solid paycheck in chaotic times, he goes to college to study advertising. People will always need other people to sell them things.

He doesn’t much think about the probe, and when he does, the thoughts are not particularly happy. It was his dad who raised him. His mother spent his formative years far away, in an office somewhere, tending to her favorite child.

Fourteen Years

The probe has traveled one light-year. This far out, the Sun is only a bright star. Still, it exerts an influence—out here in the Oort cloud, numberless peaks of ice tumble on orbits millions of years long, loosely bound to the Sun’s gravity. Occasionally, perturbations from a passing star will send a hail of comets diving into the interior of the Solar System.

Space is so vast that the probe has little to fear from this debris cloud. The particle shield, angled forward for more than a decade now, has only a few small pockmarks to its credit.

Twenty-One Years

Minerva is a grandmother. Matthew and his wife Jamie welcome their new daughter, Sarah, into the world.

Twenty-Nine Years

Every year, Sarah looks forward to spending the summer with Grandma. It’s a break from her normal routine, a chance to visit an exotic part of the country, and compared to Mom and Dad, Grandma offers more treats and fewer rules.

Grandma keeps a painting of a medieval cathedral on her living room wall. A big, imposing structure, artfully crafted with an eye-watering array of details, so different from the world of concrete, steel, and glass Sarah sees when she goes into the city.

“Why did you pick an old church?” she asks one day, while she and Grandma sit together on the couch. “You’re not religious.”

Grandma smiles. Her hair has gone white, and her face is creased with wrinkles, but she has retained a kind of healthy vitality in her old age. “No. But I can still find things to admire. You know, back when they used to build cathedrals, it would take decades to complete them—hundreds of years, sometimes. The sons and daughters of the original craftsmen would carry the work forward. If you began such a project, you could never be sure that you would see the great, beautiful thing you were making.”

Sarah thinks for a moment, and makes a connection she’s very proud of. “Oh. Like your space probe!”

Grandma gives her a pat on the shoulder. “Yes, Sarah—just like my space probe.”

Thirty-One Years

The probe suffers its most severe impact yet. Something the size of a grain of sand punches through all three layers of the particle shield, and is vaporized in the process. The onboard computer runs extensive diagnostics, registering no systems failures, but it cannot rule out lasting damage.

Thirty-Four Years

From the probe’s point of view, the stars Alpha Centauri A and B are now brighter than anything else in the sky. Alpha Centauri A, very much like our own Sun, and B, a little smaller, make a tight circle around each other every 79 years. Proxima Centauri orbits a fifth of a light-year from their combined center of mass. As a red dwarf, an eighth the size of the Sun, it remains too dim to see.

Thirty-Seven Years

Sarah is a precocious student. Her hours reading from Grandma’s library have equipped her with a ravenous thirst for knowledge, and inspired the pursuit of more than a few advanced science courses in school. Her grandmother takes note; one summer, when Sarah’s in town, she takes her to visit some of her colleagues from the interstellar program. They get together every couple of years, in a reserved room in a semi-abandoned office block.

“Dad always tells me you need to let it go,” Sarah says, as she and her grandmother climb the staircase to the third floor. “He thinks you’re way too invested in this, for a project that ended decades ago.”

Minerva takes a break to catch her breath when they reach the second-floor landing. She gives Sarah a sharp look. “Do you believe that?”

“Of course not!”

“He never did get it.” Minerva smiles, though that smile quickly fades. “Though you should remember, now that I’m retired, you have the benefit of my full attention. With your father, I may have been…”

She trails off. Before long, they arrive at the meeting room. There are a few people already there, most of them as old as Minerva, and they cheer when she walks through the door. What follows for Sarah is a long series of introductions and handshakes, neither of which she’s very fond of. There’s a big man named Frederico, armed with a titanic smile, and a woman named Angela, frail and wiry. They ask her how she’s doing in school, and go on about how her grandmother was a joy to work with. Sarah is the only young person here, with the exception of Frederico’s son, Henry, who’s around her age.

This room is more like a shrine than an office. There’s a table littered with models, diagrams, and commemorative medals, and an enormous poster on one wall, laying out the interstellar probe’s flight plan. A line of photographs shows the design team’s meetups, over the years; Sarah can see the progress of old age from frame to frame. Each photo has one or two fewer people than the previous.

She has realized she admires these people, whatever her dad says. Minerva and her friends are the underground prophets of a forgotten religion, keeping the faith alive as the world passes them by. But on that glorious day, far in the future, when their beloved probe completes its mission, they will have their time in the sun again—even if none of them are there to witness it.

Forty-Eight Years

Minerva passes away in a hospital bed, at the ripe old age of eighty-six, attended by the next two generations of her family. Sarah stands right beside her; Matthew sits in a chair nearby, his head in his hands.

Fifty-Eight Years

Coming to a stop at Proxima Centauri was one of the greatest challenges faced by the mission designers. Left to its own devices, and without any engine more powerful than a small maneuvering thruster, the probe would hurtle past the target star at full speed, just like the discarded light sail before it. Interstellar space is empty in any meaningful sense. There is nothing one can push against to slow down—with one exception.

Like all stars, Proxima Centauri has a magnetic field, extending far out into space. This can be pushed against. For the final leg of its journey, the probe unspools a superconducting wire of incredible thinness, forming a ring five kilometers in radius. Electricity courses through this ring; it soon gains a charge of several million volts, creating a powerful magnetic field extending in front of the ship.

This artificial field meets the field from Proxima Centauri, still quite faint at this distance, and the effect is like an invisible parachute. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the probe begins to decelerate.

Sixty-One Years

Proxima Centauri is a bright red ember in the sky—brighter, finally, than the two much larger stars that it orbits. The probe continues its long climb down from seven percent of lightspeed. Its scientific suite is fully active, now, and its telescopes are gathering better data on this star system than has ever before been collected.

There are five planets. Three were known to science prior to the interstellar mission, and two have just now been discovered: icy, outlying bodies, one roughly Earth-mass, the other a bit smaller. The flight computer deems these worthy only of remote observation; as originally envisioned, it will focus its efforts on the innermost planets, particularly Proxima Centauri b.

Sixty-Two Years

The gentle deceleration of the magbrake has given way to the similarly gentle thrust of an ion drive. While the probe will get nowhere quickly with such an engine, it has more than enough xenon fuel to take it on long, arcing trajectories between planets. It helps that the entire Proxima Centauri system could fit within the orbit of Mars; around a miniature star, the distances are not particularly vast.

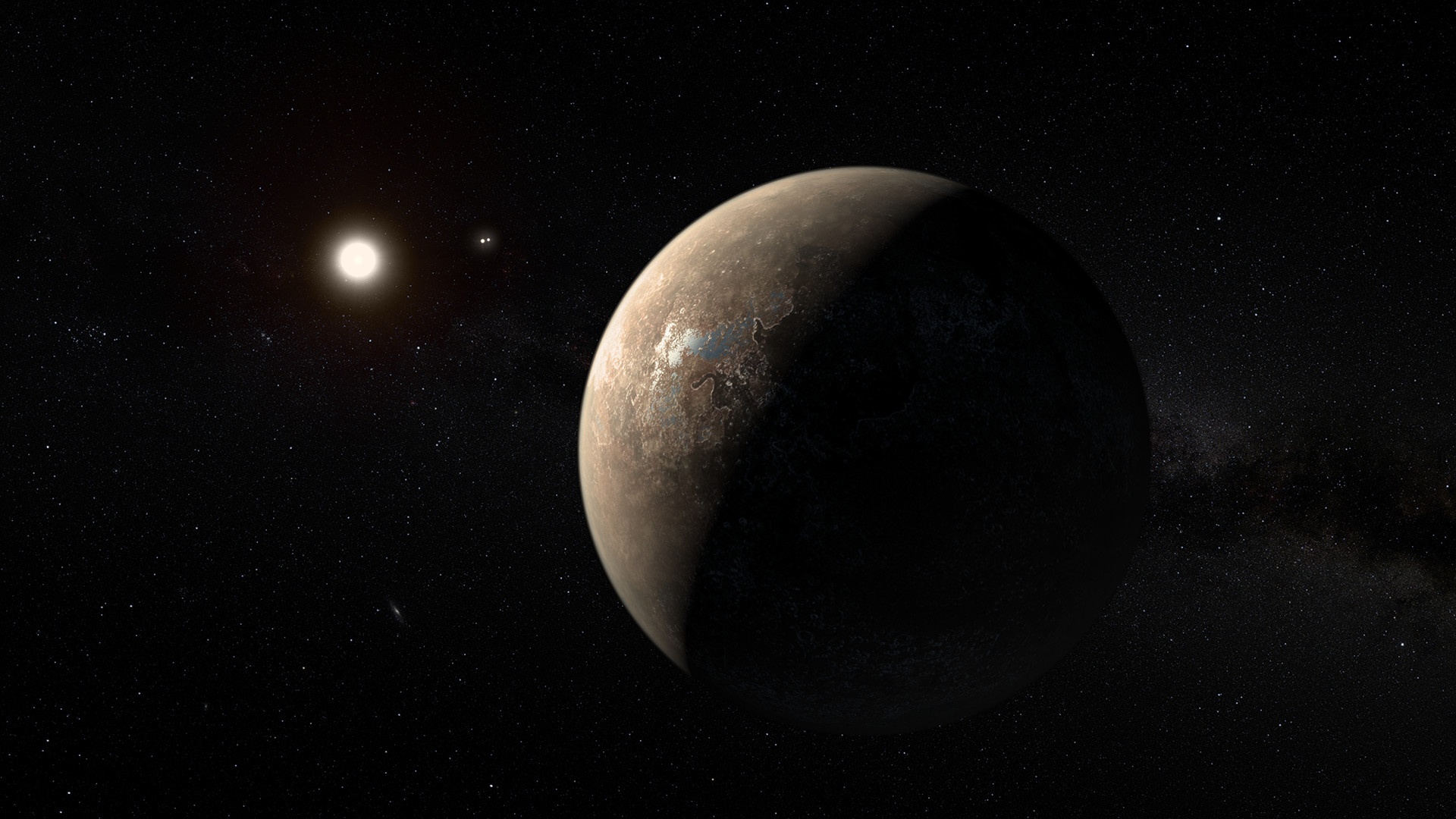

The probe is approaching Proxima Centauri b. Remote observations have revealed the presence of liquid water and a moderately thick atmosphere, the latter of which will enable a parachute landing. There are not yet any indications of life.

This is a pale, reddish world, a little larger than Earth. One side permanently faces its star, while the other is always shrouded in night, locked beneath a vast hemispherical icecap. Most of the liquid water seems to be concentrated around the border between these two regions. Any inhabitants will witness an eternal sunset, with the disk of the sun fixed in place some distance above the horizon.

The probe enters orbit, and detaches its lander—a shallow cone about the size of a washing machine, which may or may not survive reentry, damaged as it was by a debris strike thirty years ago. With fearlessness only a machine can manage, it descends towards the surface.

Sixty-Five Years

After so many decades of apathy, the world eagerly anticipates the mission’s results. Some scientists advise caution; the space probe has been silent for many decades now, and there is no guarantee that it made it to its destination, or that it successfully beamed back data. Sarah waits with bated breath. Even her father seems interested, at least more than usual. He forwards emails to her, various articles by planetary scientists and interviews with officials in the space program, and asks for her thoughts.

Sixty-Six Years

The coded beam of data took 4.25 years just to reach Earth, and researchers needed another week to process it all. Now, the space program has announced a grand unveiling of the first pictures, scheduled for Tuesday night.

Sarah receives a call from Henry. She’s seen him only a few times over the years, at meet-ups of the original design team—now all deceased—but they’ve kept in touch. Apparently, he’s organizing a watch party with some of the other descendants. Would she want to join?

She accepts in a heartbeat, even though it means a last-minute drive to another state. And while Matthew is grey-haired, by now, and dependent on a cane to get around, he goes with her.

They watch the event in Henry’s living room. It’s packed with people, but Sarah was still able to secure spots on the couch for herself and her father. For a while there’s just a panel of administrators on the screen, discussing at length the design of the probe and its successful performance, but then, almost without warning, the first image appears:

A rocky plain, cluttered with boulders and devoid of any visible life. A fat, ruddy sun hanging over the horizon. It takes only a glance to realize that it is not our sun, and this is not our solar system. The landscape beneath it is the color of rust; that may be due to the rocks themselves, or perhaps just the lighting. In the distance, at the foot of a line of hills, lies a dark expanse—liquid water?

If only her grandmother could be here to see this.

Many seconds later, when she is able to pry her gaze away, she looks over at her father. Tears are rolling down his face.

Thank you for reading! I would love to hear any feedback you have in the comments below, and be sure to subscribe, if you haven’t already, to be notified about future posts. I’ll see you fine ladies and gents next week.

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

very interesting story. Enjoyed the structure ofnit