Happy Halloween, everyone! We haven’t had a proper Halloween special since my review of Event Horizon, all the way back in 2019, so I’m here today with something appropriately spooky: a conspiracy theory. Read on to uncover tales of ill-fated missions and doomed space travelers…

First in space?

Yuri Gagarin is recognized as the first human to leave Earth, having undertaken a world-historic single-orbit spaceflight on April 12, 1961. This was the culmination of numerous unmanned test launches, which after several failures, and the deaths of a considerable number of dogs, had ironed out flaws in the one-man Vostok spacecraft. Only once the dogs started reliably coming back in one piece did the Soviet leadership feel ready to risk the life of a pilot. But what if they actually jumped the gun? What if there was someone else before Gagarin, an unfortunate soul who went up there and never came back alive? Amid the immense secrecy of the Soviet space program, which waited to announce Gagarin’s flight until after he was safely in orbit, it wasn’t out of the question—and rumors began circulating even back then.

Oberth and Heinlein

In 1959, claims surfaced in the West that the Russians had been unsuccessfully sending up cosmonauts aboard suborbital rockets. According to an unnamed intelligence source in Czechoslovakia, repeated second- and third-hand in various newspapers (such as the Gadsden Times, archived here), there were four launches from a complex near the Iranian border, all of which failed when “the Astronauts vanished into space.” No less a personality than rocket theorist Hermann Oberth gave voice to the rumors. But the alleged Czechoslovakian source was never identified, nor did any further information come to light over the following decades. We do know, however, that after World War II the Soviets were considering very similar missions using the German V-2 missile, which might have seen a Russian short hop into space as early as 1948.

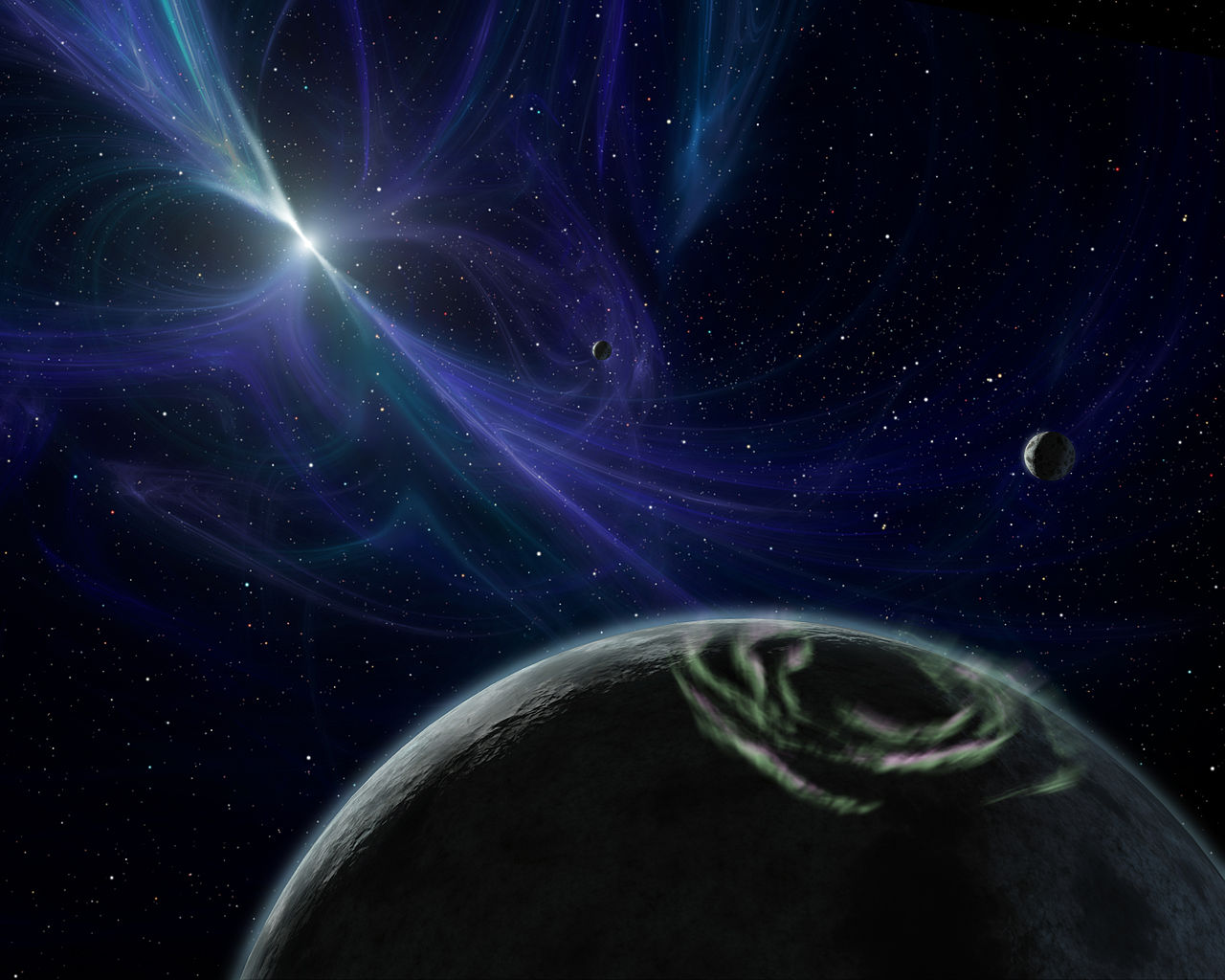

The next claim appeared in 1960, when Robert Heinlein (of Starship Troopers fame) was traveling through the USSR. On May 15, in Vilnius, Red Army cadets told him that their country had just launched a human into space—and indeed, that day had seen the launch of Korabl-Sputnik 1, the first of the Vostok test flights, which failed to return to Earth after a retrorocket malfunction sent it into a higher orbit. Heinlein suspected that the officially “unmanned” mission had in fact carried a pilot aboard. The poor soul would have died only a few days after launch, when his life support inevitably ran out; he would have remained up there until his ship naturally deorbited in 1962.

The peculiar adventure of Vladimir Ilyushin

Vladimir Ilyushin was one of the Soviet Union’s most renowned test pilots. He was so skilled, in fact, that he once seized up a plane’s computer by flying too precisely1. Such was his reputation that the military entrusted him with the maiden flights of an entire generation of aircraft, from interceptors to tactical bombers—and, perhaps, that of the Vostok space capsule, beating Yuri Gagarin by a mere five days.

This conspiracy theory originated with an article in the British communist newspaper The Daily Worker, published April 10, 1961. Its author, Dennis Ogden, claimed that Ilyushin had flown into orbit on April 7, sustaining serious injuries in the process—injuries which were covered up by an official announcement that he had been in a car crash. Other outlets soon picked up on this theme, triggering a small frenzy of speculation. US News and World Report claimed that Gagarin had never flown in space at all, being used only as a public-facing prop to cover for the wounded Ilyushin.

A 1999 documentary, The Cosmonaut Cover-Up, articulated what came to be the standard version of the Ilyushin claims. The mission was said to have launched on April 7, as The Daily Worker originally reported. Ilyushin took off without incident and orbited the Earth three times, only to lose contact with ground control on the third pass, and after an emergency firing of the retrorockets he made a hard landing thousands of kilometers off course—within Chinese territory. Shared communist ideology notwithstanding, the Soviet Union and Red China were not friends. Ilyushin was held captive for more than a year until the Soviets secretly negotiated his release. Meanwhile, Gagarin had become the face of the Soviet space program, falsely trumpeted as a pioneer to spare his country the humiliation of a rocky first spaceflight. Gagarin’s death in a 1968 training accident was just part of the coverup.

Despite its persistence, the Ilyushin theory has met with considerable skepticism. Ilyushin himself, who died in 2010, steadfastly denied ever having gone to space. The actual evidence is thin on the ground—hearsay, mostly. And as space historian Mark Wade has pointed out, it’s hard to explain a secret mission when the period around Gagarin’s flight is so well-documented (an issue with most lost cosmonaut stories, as I’ll discuss at the end). To me it seems more than a little unlikely. Then again, there’s nothing technically implausible about the theory; the Soviets were fully capable of launching a cosmonaut shortly before Gagarin, and a crash landing in a hostile country would have been reason enough to keep it secret. As they say: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Signals from doomed ships

Then there is the case of the Judica-Cordiglia brothers. Based in a former German bunker outside Turin, Italy, and equipped with an improvised radio set, they claimed to have intercepted and recorded signals from a variety of early Space-Age craft. Ominously, some of them appeared to be human voices, pleading for help. Mere weeks before Vostok 1, they picked up a transmission from a female cosmonaut:

“I can see a flame! Thirty-two… thirty-two. Am I going to crash? Yes, yes I feel hot… I am listening, I feel hot, I will re-enter. I’m hot!”

And the signal ended. Was this a real human being, alone and terrified beyond the Earth’s atmosphere? Did she perish as her ship broke up on re-entry? According to the paranormal magazine Fortean Times, the brothers picked up eight secret cosmonauts between May 1960 and November 1964. Some seemed to vanish into deep space, drifting out of Earth’s orbit into the great beyond, while others went dark during atmospheric entry, or suffocated after the failure of their life support. It was as if there was a whole shadow space program, sending cosmonauts to their deaths between the successful flights that the Soviets so triumphantly hailed.

The Judica-Cordiglia brothers’ recordings have received considerable criticism over the years, and not without good reason. None of the alleged cosmonauts used formal radio protocols—strange, for a group that we know was drawn from elite pilots, representing the Soviet Union’s brightest and most disciplined aviators. And some of them spoke an accented form of Russian, not that of a native speaker. Could it have been a forgery? If the signals weren’t genuine, that is the obvious explanation. But Giovanni Judica-Cordiglia, the surviving brother, stands by his story over sixty years later—and the debate has not been resolved one way or the other.

Want to decide for yourself? You can find the original recordings archived here.

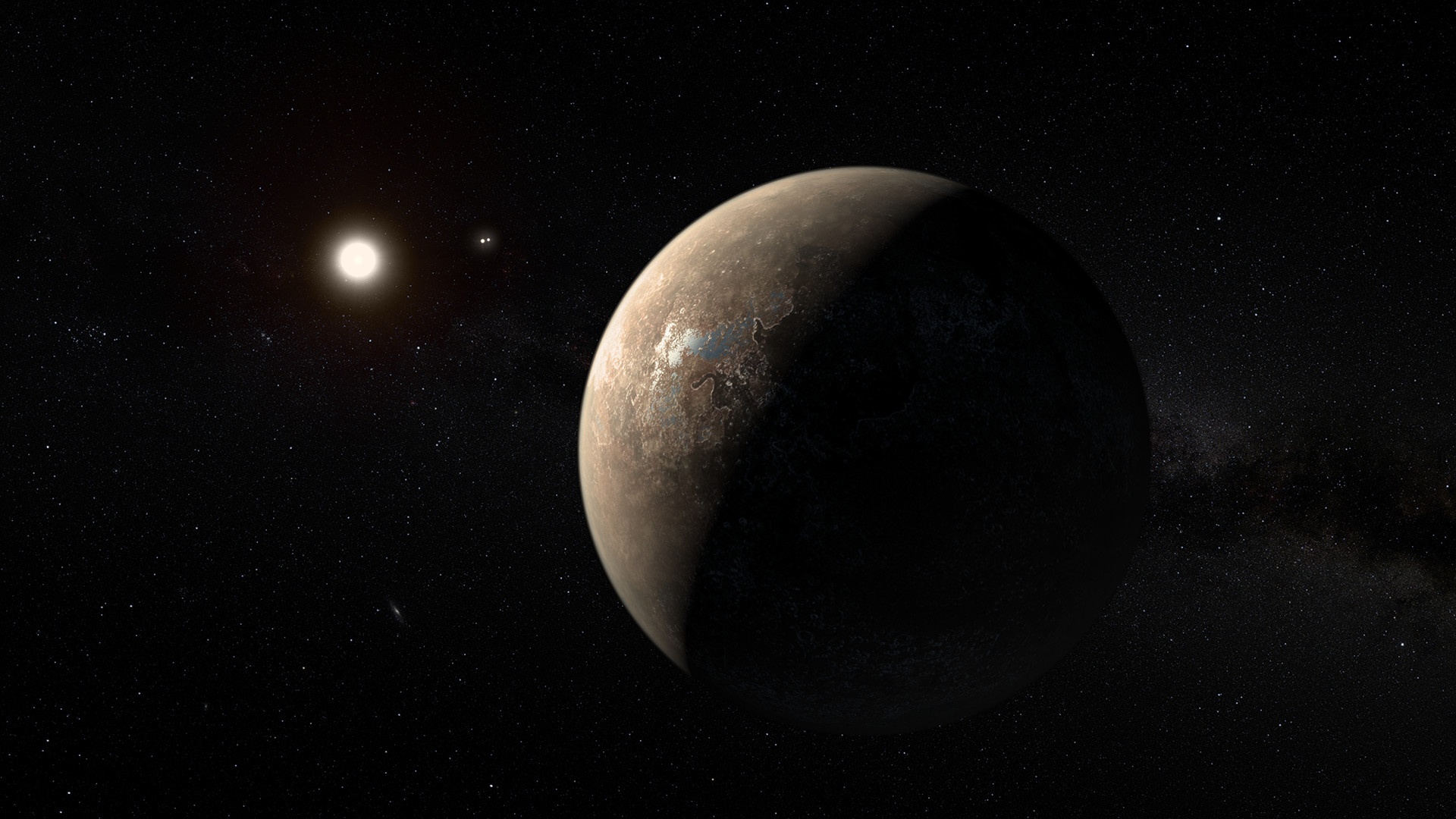

A secret moonshot

We have discussed lurid tales from the dawn of space travel: failed suborbital hops, Vostok missions gone horribly wrong. But the flurry of lost cosmonaut speculation does not end there. If Earth orbit harbors its secrets, so, too, might the Moon—the nearest world to our own, and the finish line of the Space Race, even if the Soviets later insisted they had never aimed for it. The Soviet lunar program was itself covered up by the authorities; vehicles such as the thundering N1 booster2 and the insectoid LK moon lander only came to light in the late 1980s, after two decades of airtight secrecy. What else could they have been hiding?

For a while, the Soviets had a lunar program almost matching that of the Americans. Their probes achieved some stunning successes, such as Luna 9, the first spacecraft to make a soft landing on the Moon; Luna 16, the first unmanned sample return; and Lunokhod 1 and 2, the first remotely controlled rovers to drive on another world. They were still flying missions there in the mid-1970s, after Apollo had packed up and left. Where they couldn’t compete, however, was in the arena of actually placing a man on the lunar surface. The keystone of the Soviet moonshot, the N1 super-heavy booster, ultimately proved to be its undoing—they simply never got the thing to work, and thus never had an answer to NASA’s Saturn V. Four test launches between 1969 and 1972 ended consistently in disaster, with one of them numbering among the largest non-nuclear explosions in history. Ultimately the Soviets gave up trying and concentrated on space stations in Earth orbit.

None of that, however, has stopped speculation that the Soviets secretly landed humans on the Moon, or at least launched them in that direction. It has been said3 that the second, unmanned test launch of the N1 was not unmanned at all; this flight, which took place on July 3, 1969, was actually a desperate attempt to beat the Americans to a moonshot, with two ill-fated cosmonauts climbing into the rocket and hoping for the best. According to the story, these secret moon travelers perished in flames when their N1 exploded beneath them. It is well established, though, that the launch escape system of that test flight functioned perfectly, delivering the capsule to a safe distance. If the Soviets did take that opportunity for a last-ditch moonshot, the cosmonauts walked away from it in one piece; presumably, they were sworn to secrecy, and the whole embarrassing episode was swept under the rug.

Another story comes from the Russians themselves. In the early 1970s, rumors went around Moscow that the Lunokhod rovers were not remotely piloted from Earth, as the government claimed, but driven by very small KGB agents who had been sent to the Moon on suicide missions. Apparently the poor state of Soviet electronics left no other explanation. This one is ridiculous on the face of it—there was no way a washtub-sized Lunokhod could have supported a man for months on end—but to be fair, one-way moon missions have been proposed before.

And there are even weirder claims out there—such as the assertion that Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov flew to the Moon in total secrecy, aboard an American spacecraft, as part of a joint US-Soviet Apollo4 mission dispatched to investigate a crashed alien starship. The Apollo 20 conspiracy theory has been circling around the internet since the early 2000s; while the whole thing was exposed as a hoax, with the supposed “footage” being no more than elaborate modelwork by a French prankster, you’ll still come across people who swear by it. At least it’s a good deal more interesting than your typical moon landing conspiracy theory, which insists we never went. I’ll happily take lost cosmonauts and aliens over Kubrick filming astronauts on a sound stage.

Known deaths and coverups

Aside from all the theories I just presented—some of them rather far-fetched—it is well established that the Soviet space program saw a number of cover-ups, and, indeed, the deaths of multiple cosmonauts. The first fatality occurred on the ground, just three weeks before Gagarin’s flight. Valentin Bondarenko, the youngest of the first cosmonaut class, was performing a fifteen-day experiment in a pressure chamber when his clothing caught fire, ignited by an electric hot plate. High oxygen levels meant that the flames spread quickly and ravenously. He suffered severe burns over most of his body—to the point where the attending doctors, seeking intact skin where they could place an IV needle, had to use the soles of his feet—and he died in the hospital sixteen hours later. The authorities concealed this tragedy by airbrushing him out of photographs and falsifying records. Bondarenko’s death remained a tightly guarded secret for more than two decades, until a liberalizing Soviet government finally admitted the truth.

Bondarenko was not the only cosmonaut to be wiped from history. Note the two photos above—the vanishing cosmonaut is not Bondarenko, but another man, Grigori Nelyubov, who got into a drunken brawl and disgraced the program. Naturally, the Soviets tried to save face by pretending he had never existed. According to a 2011 exposé in WIRED, this was a widespread practice in the Soviet space program, though investigations into the missing cosmonauts have revealed that they were discharged for mundane reasons: bad behavior, medical problems, the like.

The highest-profile cosmonaut death in the Space Race days was that of Vladimir Komarov, who flew aboard the first mission of the Soyuz capsule on April 23, 1967. Soyuz 1 was a disaster even before it took off; despite warnings that the spacecraft wasn’t ready, Party leaders pressed ahead with a launch in time for the anniversary of Lenin’s birthday. Once in orbit, a solar panel failed to deploy, starving the ship’s systems of power, and problems with attitude control meant that Komarov couldn’t even keep his craft pointed the right way. Eventually mission control scrubbed the mission and told him to come home. Komarov might have landed safely, if not for another critical defect: the drogue parachute got tangled with the main parachute, keeping it from deploying, and his capsule slammed at full speed into the Russian steppe.

Komarov’s flight was widely known at the time—he was no lost cosmonaut. Nevertheless, the Soviet government was not forthcoming with details, and as they released a polished statement for the public, lauding him as a hero and burying him in the Kremlin Wall, they did everything they could to hide the string of oversights, design flaws, and general negligence that had led to his death. The prestige of the Soviet Union could not be tarnished; one suspects that if they’d had a chance at concealing the accident altogether, they might have tried it.

Dubious claims (but a great story!)

A few years back, I watched some episodes of Ancient Aliens with my then-girlfriend, who was avidly into UFOs. The show presented outlandish claims of alien incursions, lost continents, secret messages encoded in history; she believed every word of it, and while I knew I was being fed slickly produced nonsense, I had to admit there was a certain draw. However much my brain poked holes in the theories on display, it was exciting to live in a world where unknown, otherworldly forces lurked behind mundane events.

Lost cosmonaut stories scratch a similar itch for me. I’m a sucker for mystery, in general, and tales of doomed Soviet space missions in particular. It’s just such a fascinating image: a man trapped in the confines of a Vostok capsule, hurtling away from Earth into the unknowable gulfs beyond, stranded, alone, his breaths growing ever slower, ever fainter as his life support gives out… and in the end he is buried in history, his very existence denied by a secretive regime that can’t afford to lose face. Great material for a short story, I should think. Whether it actually happened is another question—and on that count, you can color me skeptical.

The problem is that the Iron Curtain eventually came down, bringing with it the veil of secrecy that had kept so many things hidden from the West. We now have detailed knowledge of nearly everything that went on in the Soviet space program, from design work to cosmonaut recruitment to the missions themselves, and amidst all that data there is scarce room for phantom flights. If cosmonauts went into space before Gagarin, who were they? Everyone seems pretty well accounted for—even the men who were airbrushed out of official photographs. The Vladimir Ilyushin story at least names a known individual who could plausibly have been chosen to go into space, but there’s still no real evidence linking him to the cosmonaut program, nor did the US or any other nations track his alleged launch. And the moonshot allegations are dreadfully thin, as tantalizing a prospect as they might present.

My view is that the actual facts of human space travel line up pretty well with the accepted narrative. Despite the stories—and in one case, radio recordings—space history has few holes large enough to fit a lost cosmonaut. I could be wrong, of course; the truth has a way of being more surprising than expected. But the genre of lost cosmonaut theories is by and large a mirage, best as creepy tales to tell around a campfire—or as fodder for Halloween-themed blog posts.

Thanks for giving this a read, everyone. If you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe–and happy Halloween! I wish you all a great time with your tricking, treating, and general festivities.

- The aircraft’s guidance system was programmed to compensate for deviations from the expected flight course. When there was no meaningful deviation, thanks to Ilyushin’s expert piloting, the computer didn’t know what to do—and crashed. Presumably he flew the rest of the way home with analog controls. ↩︎

- Some fun trivia for you: Until the launch of SpaceX Starship this past April, the N1 had the most powerful first stage of any rocket ever flown. ↩︎

- By whom, you ask? Unclear. The only reference to this claim I can find appears on Wikipedia—and is flagged with a big fat “Citation Needed.” But dammit, it’s a good story! ↩︎

- Those of you who have been following this blog for a long time may remember that I once wrote a post on this. It was a good post, and I’m still proud of my work, but there was one problem: it attracted overwhelming traffic from genuine UFO conspiracy theorists. To keep them from flooding my site and diluting my genuine readership stats, I took the whole piece down. Some say you can still find it by following the right trail of hyperlinks… ↩︎

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fascinating stories! What about lost ground crews 🙂

Yes—plenty of material there I didn’t use! You know, the Nedelin disaster is probably going to get its own post, one of these days…