The good news is, nature has provided us with a planet startlingly similar to our own, orbiting almost within reach just 4.3 light-years from Earth. The bad news? It might not be a very good neighborhood. Despite being the best-studied exoplanet out there, scientists can scarcely make heads or tails of what it’s really like, and its potential for life is the subject of ongoing controversy. For today’s post, we’ll find out what we can about this vexing world: Proxima Centauri b.

Close to home?

The star Proxima Centauri is so named1 because it is the nearest star to Earth (besides the Sun, of course). As of 2020, its distance is estimated at 4.2645 light-years, or about 40 trillion kilometers. That’s quite a long way. If you want to wrap your mind around it, imagine this: you’ve shrunk Earth down to the size of a pencil eraser, barely more than a centimeter across, and you’re holding it in the palm of your hand. Its miniature Moon is a sesame-seed-sized object about a foot away from you. The Sun is down the street, and Pluto is on the other side of town. If we keep following this scale, how far is it to Proxima Centauri?

Proxima Centauri is on the Moon. By which I mean the real Moon, 384,000 kilometers away. So… pretty far.

But also pretty close, as far as stars go. The next-closest ones to Earth are Alpha Centauri A and B, a pair of broadly sunlike stars some 4.344 light-years away. Together they form a trinary system with Proxima Centauri, which circles the Alpha Centauri A-B center of mass at a distance of 0.2 light-years, and takes a whopping 550,000 years to make a single orbit. Proxima is so distant from its companions that there was controversy about whether it was even bound to them in the first place. More recent scholarship has determined that it is, albeit weakly.

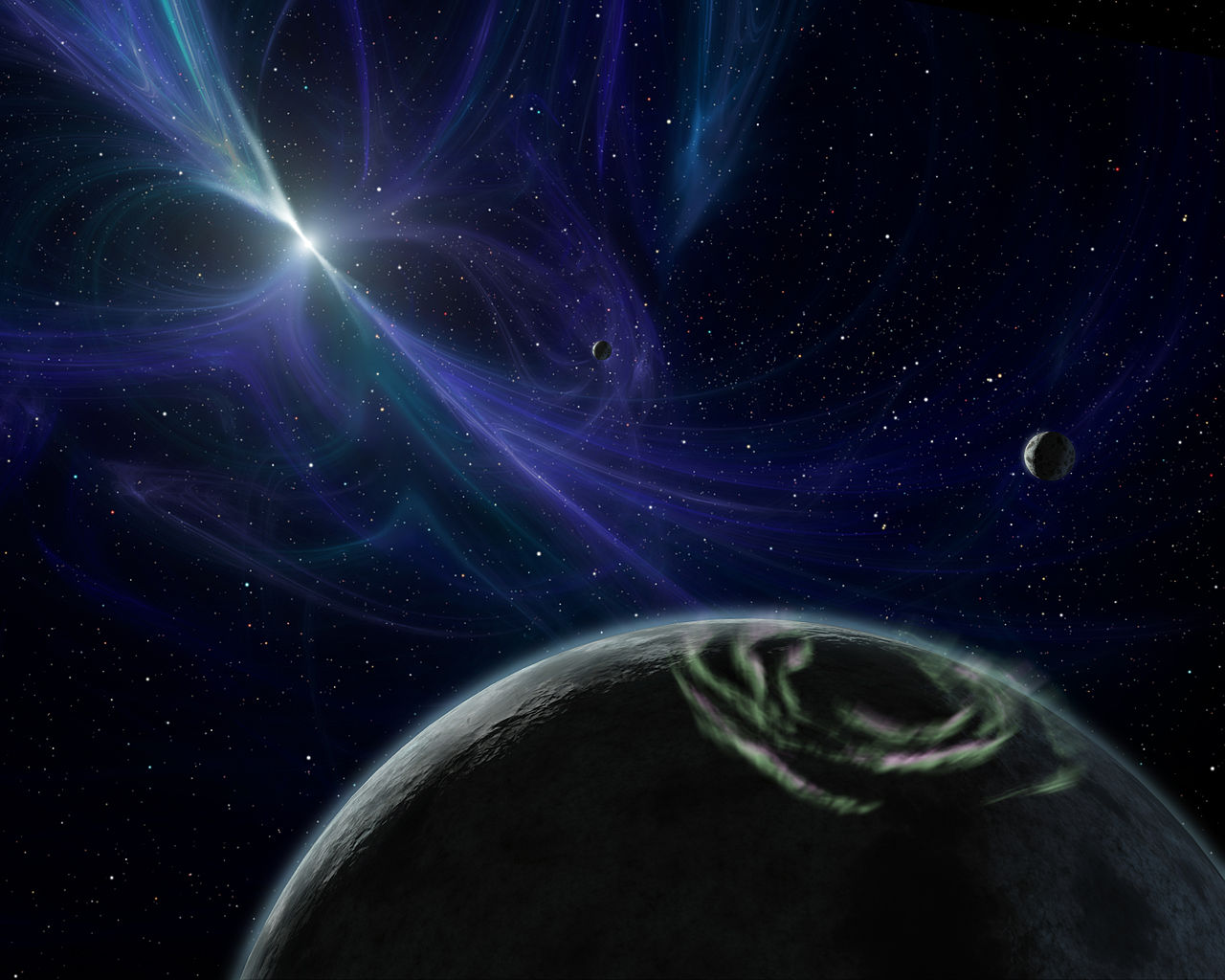

Unlike Alpha Centauri A and B, Proxima Centauri isn’t much like our Sun at all. It’s what astronomers call an M-type red dwarf, small and dim, just 12.5% as massive as the Sun and less than one percent as bright. Despite its nearness to Earth, it can only be seen with a telescope. And despite its dimness, it’s prone to throwing tantrums: periodically, it will flare up to dozens of times its usual brightness, spewing X-rays and other radiation out into space. This behavior is common for red dwarfs. Since they’re so small, the stellar material in them mixes more easily, which creates strong—and violent—magnetic fields2.

Discovery, and early hopes

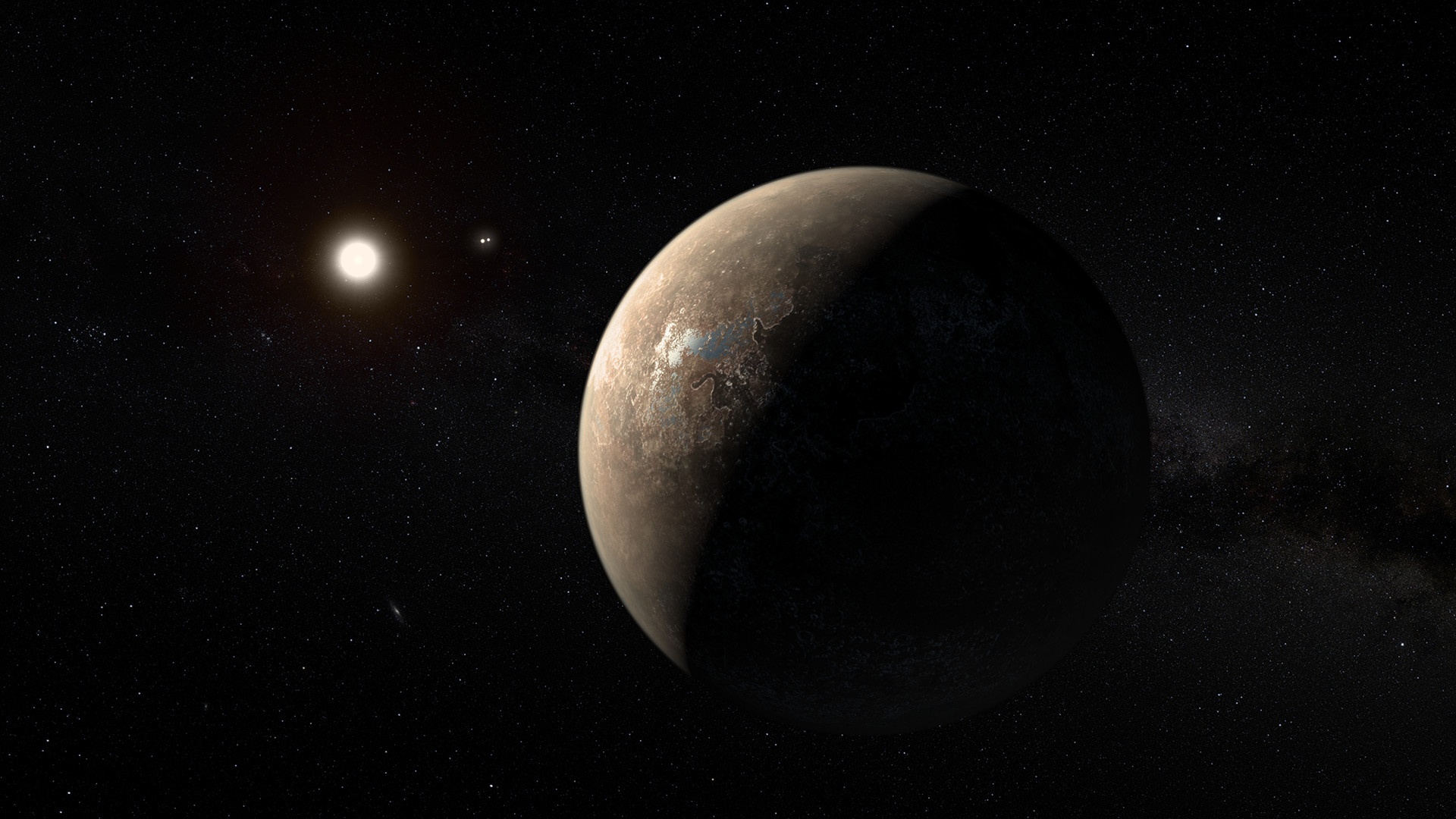

Appropriately for its location, Proxima Centauri has long been a target of exoplanet research. Efforts finally paid off in the summer of 2016, when astronomer Guillem Anglada-Escudé and his team, based at the European Southern Observatory, announced the discovery of a larger-than-Earth-sized (super-Earth) planet orbiting the star. It was named Proxima Centauri b, per convention; a more poetic name has yet to be bestowed. Their discovery caused much excitement, especially since Proxima b3 lies within its star’s habitable zone—not so far away that water would freeze, yet not so close (in theory) that it would boil off. It looked very much like it might be a twin of Earth, hosting seas and an atmosphere. Life, even.

Keep in mind that Anglada-Escudé’s team didn’t just point their telescopes at Proxima b and say “Behold, a planet.” While we can look straight at the worlds in our own solar system, those around other stars must almost always4 be observed indirectly, using a variety of methods which I will not belabor here. In the case of Proxima b, astronomers carefully examined the star’s light spectrum over a period of several months. Certain changes in its spectrum were identified as Doppler shifts, caused by motion towards or away from Earth, and, with these, they could calculate subtle changes in the star’s velocity. Plotting these velocities revealed the gravity of a planet, tugging Proxima Centauri back and forth.

It’s a bit like… say, tracking a plane that’s flying above you at 30,000 feet. And you have a very good telescope, so you look through one of several windows, carefully watching the face of the passenger in the aisle seat—and, just from the reflections in their eyeballs, you deduce what in-flight movie they’re watching. Except considering the scales and distances involved, exoplanet research is even harder than that.

Life around a red dwarf

We still know very little about Proxima b. The radial velocity method, above, only gives us the minimum5 mass of the planet—at least 1.07 times the mass of Earth—and its orbital period—11.187 Earth days. Based on the period, we can pin the radius of its orbit at 0.0486 astronomical units (AU). One AU is the distance between Earth and the Sun; transplanted to our own star system, that would place it deep within the orbit of Mercury. Only because Proxima Centauri is so small and dim can Proxima b avoid being burnt to a crisp.

We can infer some things from this situation, and most of them are weird. For one, Proxima b probably doesn’t have moons—the gravity of its sun, so close by, would have long since knocked them out of place. For another, astronomers believe it is tidally locked, meaning its rotation is in sync with its orbit. If the orbit is eccentric enough, this could imply what’s called 3:2 resonance, where it spins three times for every two orbits around Proxima Centauri; Mercury has that kind of arrangement with the Sun. Most likely, though, Proxima b is in a 1:1 resonance, pointed rigidly at its local star, the same way the Moon always shows one face to Earth.

Standing on the day side of Proxima b, you’d see the sun hanging motionless above the landscape. You can wait eight hours, or eight years—there will be no sunset. It looks several times larger than the sun back home, and it dominates the sky. The small size of Proxima Centauri is more than made up for by its close distance to Proxima b. And its color? An eerie orange, surprisingly dim despite the heat you feel. M-type stars put out most of their energy in the infrared. As a result, any plants you’ll see will be jet-black, desperate to soak up as much light as they can.

Much of the day side is a scorching desert. Walk long enough, though, and the sun will sink ever lower in the sky, cooling the land, until you arrive at a twilight zone on Proxima b’s terminator. Here, it’s always sunset. This is the region most likely to support life. Perhaps you see forests, so many trunks with black leaves that all face the same way. Maybe you pass by the shoreline of a small, placid lake, where nameless creatures swim in the darkness beneath the water. Maybe you even find people—settlers, humans, eking out a precarious existence on this strange new world.

Continue further, past the sunset. The red skyglow will recede behind you, dimming to nothingness, immersing you in perpetual night. You’ve stepped onto a glacier that stretches for twenty thousand miles. The stars hide behind a black sheet of cloud. Around you: hurricane-force winds, scraping your skin with icy pellets. Snowdrifts as large as cities. The sweeping expanse of a shadow realm, colder than Antarctica, darker than the deepest cave, unseen and unremarked since the beginning of time.

Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

Cloudy with a chance of X-rays

The picture I’ve just sketched is the conventional view of a red-dwarf planet, and for a while it was the dominant assumption for Proxima b, too. But more recent research has called it into question. Far from a strange but habitable super-Earth, Proxima b may be an airless, irradiated rock—no abode for life whatsoever. The issue lies with the sun it orbits. Proxima Centauri is… temperamental, to say the least.

Remember those flares I was talking about earlier? They’re nothing to sneeze at. Proxima Centauri glows with UV and X-ray radiation, spitting out huge bursts at unrelentingly close intervals. A recent study detected as many as 463 flares during 50 hours of analysis. Since Proxima Centauri is entering stellar middle age6, at around 4.9 billion years old, it would have been even more active in the past, when any life would have first evolved on Proxima b. Whether anything could have survived such a barrage is an open question.

The constant radiation blasts also bode ill for an atmosphere, which may have long since been stripped away. Here on Earth, orbiting a star that is much less prone to tantrums, we’re sitting pretty behind our magnetic field; nobody knows if Proxima b has such a field, or if it does, whether it’s remotely strong enough to stand up to a solar wind ten thousand times stronger than ours. Traditionally, tidally locked planets have been assumed to be geologically dead, and thus lacking magnetic fields. A study by geophysicist Peter Driscoll suggests the contrary: tidal heating mechanisms may actually produce strong magnetic activity in planets like Proxima b, shielding them somewhat, though how much isn’t clear.

The jury is still very much out on this one. We know Proxima b’s orbit and (rough) mass, and we know many of the characteristics of the star it orbits, but we can only speculate as to how all those factors interact. Right now it seems like a battle between Proxima Centauri’s ferocious atmosphere-stripping radiation, and various protective factors that may or may not exist. We can only find out by continuing our observations, learning as much as we can through bigger and better telescopes—and, perhaps, by going there.

Crossing the gulf

The close location of Proxima Centauri makes it the obvious first stop for any dreams of interstellar travel. But that’s not an easy task. Interstellar space is just so vastly, unreasonably huge, it would just swallow up any of the spacecraft we have launched to date, without any hope of them reaching their destination within our lifetimes, or even the lifetime of human civilization. The probe Voyager 2, which left the Solar System in 2018, would take more than 75,000 years to get to Proxima Centauri. If we want to explore another star system, we’ll need something much, much faster than chemical rockets could possibly offer.

Thankfully, there may be such options on the table. I won’t go into the weeds on interstellar flight—that subject could take up many, many blog posts—but there have been schemes to explore Proxima b in the relatively near term, using technology close to what we have today. The trick is to use lasers. Light exerts pressure, and with enough light, focused on a sail, you can accelerate a low-mass spacecraft very, very fast. “Interstellar” levels of fast, potentially.

This gets around the trickiest problem of spaceflight, which is packing enough fuel for the trip. A laser sail doesn’t need to carry fuel. An extreme example of this is the fictional ISV Venture Star, above, but lasers could enable a lightweight interstellar probe within just a few decades. A billionaire-funded project called Breakthrough Starshot has done research into this; they propose launching a whole fleet of miniaturized, laser-launched starships, each no larger than a postage stamp, which would fly past Proxima b at 20% the speed of light. That’s only a 20-year journey, plus another four for the signal to get back to Earth. Some of us alive to day would actually live to see it.

The light of another sun

Proxima b is an enormous question mark, tantalizingly close. All we really have is that signal from its host star—that slow, steady Doppler effect, rising and falling every 11 days, indicating the pull of a nearby planet. For everything else, the best we can do is make educated guesses. Personally, I have a hunch that the true nature of Proxima b is something we haven’t even imagined yet, something quite unlike all the theories I’ve discussed today. Nature has a way of throwing surprises at us.

I do hope that the more pessimistic simulations are wrong; that despite being sandblasted by solar flares, Proxima b has somehow retained a thick atmosphere, and with it, water. I’d much prefer to see lifeforms—cool ones, with scales and claws and razor-sharp teeth. Maybe some of those creatures have made themselves a civilization. They would only ever see the stars if they launched an expedition to the night side, braving the ceaseless cold for a glimpse of the heavens; to them our Sun would shine a pale yellow, maybe the eighth- or ninth-brightest object in their sky.

Maybe the universe is just as mysterious to them as it is to us. Maybe they have watched that star, that bright dot in the constellation Cassiopeia, and they are wondering, even now, whether there are planets around it.

Thanks for taking a look at this one, folks. It was tons of fun to research and write; I hope you had just as much fun reading it. If you’d like to see more of my work—in-depth space voyages like this one, reviews of sci-fi books and movies, and exclusive short fiction—be sure to subscribe for updates by entering your email below. Until next time!

- There’s an interesting wrinkle to this, actually. Proxima Centauri was discovered in 1915 by South African astronomer Robert Innes. He noted that it was near Alpha Centauri, then understood to be the closest star to Earth, and it shared the same proper motion (absolute movement through space). Two years later he named the new star Proxima, because he thought it was closer than Alpha. This was just a guess on his part; Innes didn’t have the tools to measure Proxima’s distance with any precision. Eventually, though, observations by other astronomers proved him right. ↩︎

- Those curious to learn more might refer to a blog post I wrote on the subject. ↩︎

- From here on I will use the abbreviated form, to save some wear and tear on my keyboard. ↩︎

- Direct imaging of exoplanets is extremely hard to pull off. It requires a particularly bright planet, dim star, and/or large separation between the two, or else the planet is lost hopelessly in its sun’s glare. New and better instrumentation may change things, however. ↩︎

- Why not a maximum? Radial velocity only measures how much the star is moving towards or away from Earth. The 1.07 Earth-mass figure assumes Proxima b is passing more or less between us and Proxima Centauri, in which case we’d see the full effect of its gravity. If the planet’s orbit is tilted, passing above and below the star from our perspective, it will pull the star in directions we can’t observe—and such a planet would have to be more massive to explain the motion do observe. Thus, a large planet with a high inclination would look the same to us as a small planet with no inclination. We simply can’t tell! ↩︎

- Middle age lasts a while, in this case; Proxima Centauri will still burn four trillion years from now, long after the Sun has cooled and died. ↩︎

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply