Ah, to live in the old Solar System, before our nosy little space probes pushed back the veil and revealed the other planets to be absolute shitholes. Venus was, beneath its clouds, a steamy paradise world full of lush vegetation and primordial beasts; Mars, meanwhile, was one vast desert crisscrossed by canals, pockmarked by the sandy, weathered citadels of a civilization long past its prime. Now we know better. But didn’t things have a certain romance, back when the imaginations of science fiction writers far outpaced the march of science? What’s more glamorous—a stranded Matt Damon growing potatoes in his own dung, or a muscle-bound John Carter adventuring across red plains and strange cities, battling ferocious four-armed foes, until finally he saves the day and wins the heart of a beautiful Martian princess?

Today’s piece is about the second of those offerings. I recently finished Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1912 novel A Princess of Mars, the first installment in the sword-and-planet Barsoom series. These days the franchise may be best known for the 2012 box office bomb John Carter, starring Taylor Kitsch and Lynn Collins, which lost Disney about two hundred million dollars. I maintain that John Carter is not nearly as bad as they say, but that’s a review for another time; in this post, we shall explore the original novel, and weigh dubious literary quality against good, pulpy fun.

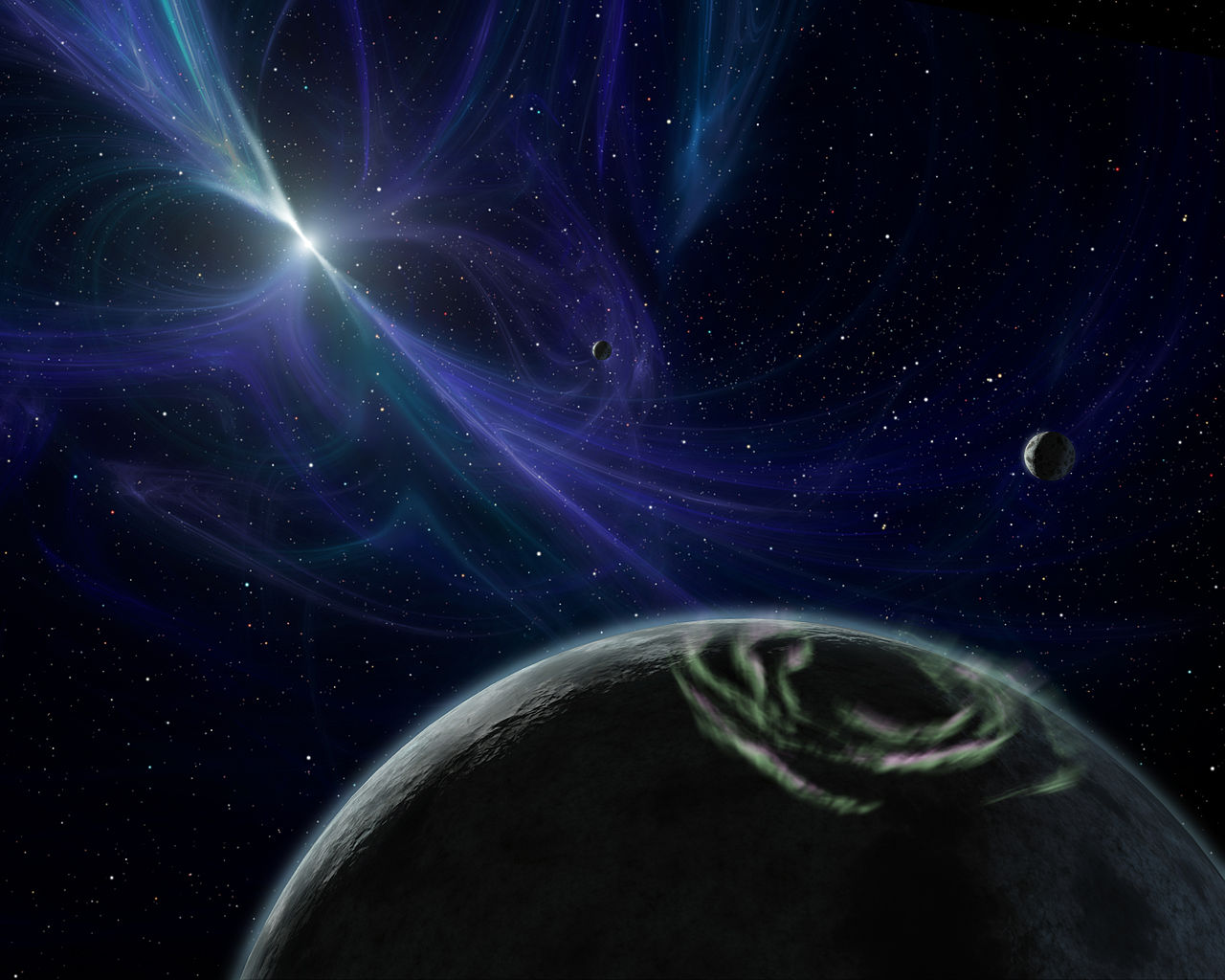

Our hero is John Carter, a washed-up veteran of the Confederate Army who goes west to Arizona in an attempt to make his fortune. Native Americans attack while he and a business partner are prospecting for gold; after a pitched engagement, Carter seeks refuge in a cave, only to discover that he has wandered into the abode of some strange, terrible power—and that his adventure is only beginning. The next thing he knows, he is transported to the yellow, mossy plains of Mars. His welcoming committee looks something like this:

Carter has happened across a party of so-called Green Martians—tall, imposing, four-armed warriors, whose migratory warbands wander amid ruined cities and dried-up seabeds left over from ancient times. Fortunately for our hero, he has a decisive advantage: the low gravity means his strength is several times that of a native Martian. With a demonstration of martial prowess he impresses the Martian chieftain, Tars Tarkas, and he follows the group back to their encampment.

Among these strange aliens, he receives a training in their customs and ways of war. Carter is not allowed to leave, making him a quasi-prisoner, but otherwise he is shown a considerable degree of respect, particularly after he kills one of their chieftains—earning title to his defeated foe’s rank and possessions. Such is the way of the Green Martians, for whom personal attachments are viewed as weakness and might makes the ultimate right. Nevertheless, he befriends a kind-hearted Martian woman, Sola, and a saw-toothed, ever-loyal Martian dog, Woola.

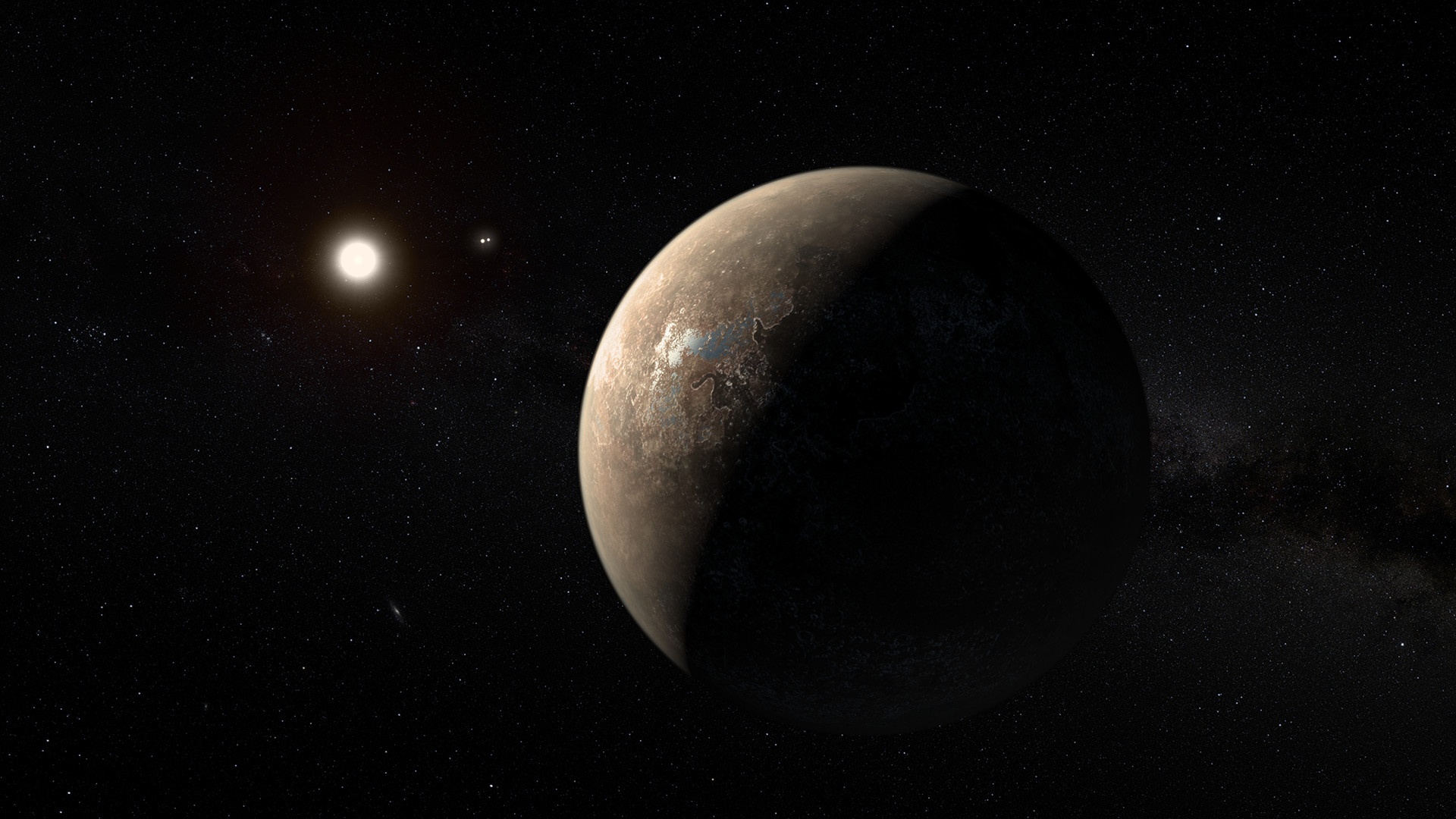

He also picks up a love interest. When the Green Martians ambush a fleet of airships that fly by their position, they take prisoner a Red Martian princess, Dejah Thoris, from the realm of Helium. Now, the Red Martians are markedly different from their green brethren; they are virtually identical to humans, save for reddish skin (and a few other details1), and while the Green Martians live in warlike bands, the Red Martians inhabit large, prosperous city-states, overcoming the planet’s harsh conditions with advanced technology. Carter is amazed that such humanoid beings can be found on another planet. More than that, he finds himself immediately smitten with the beautiful Dejah Thoris, and vows to do everything in his power to free her from her four-armed captors.

I will not belabor the rest of the plot—I’ll only say that there’s a lot of it, with a bewildering series of fights, escapades, and other brushes with death packing the pages of what is not a particularly long novel. That is, of course, precisely what you’d expect for a swashbuckling tale of planetary adventure. John Carter hurtles his way through the varied places and cultures of the Red Planet, defeating vile foes, befriending noble allies, and ultimately, rising from the bottom to make a name for himself.

Some aspects of the setting are inspired. The portrayal of Mars as a dying world was spellbinding to me, and I loved the descriptions of dried-up sea basins, vast and trackless, surrounded by ruined cities that once were ports. Far from the rocky expanse one might expect, the planet is actually covered from pole to pole in yellowish moss. This stuff can be harvested for trace amounts of moisture, vital on a world with almost no surface water, and it also has some surreal effects—nobody leaves behind tracks as they walk, while padded footfalls mean an army can march in near-total silence. Also captivating are the descriptions of Mars’s two moons, Phobos and Deimos, racing through the sky. Nights range from pitch black to eerily bright depending on how many of them are up at one time. Everywhere the world of Barsoom is deliciously exotic, rich with strangeness.

Not all of the strangeness is good, however. Edgar Rice Burroughs seems to have built the setting with a shotgun approach, spraying ideas in the hope that some of them would hit, and the result is as uneven as you would expect. Some aspects strain belief even in a novel that is so straightforwardly fantastical. For instance, all Martians are said to speak a single language—they may be green or red, or live on opposite sides of the planet, but they can all understand each other. The reason for this farcical contrivance is never explained. It’s a matter purely of narrative convenience, enabling newcomer John Carter to make his way more easily as he explores Barsoom. And for another ridiculous detail, the Red Martians protect their houses at night by raising them on poles high above the ground, never mind that this is a setting with ubiquitous flying vehicles.

As with the setting, the stylistic elements of A Princess of Mars are a mixed bag. Burroughs’ prose is severely purple, though it does have its moments of beauty, and on the whole I found it surprisingly quick to get through. The dialogue is easily the worst part. It ranges from overwrought to torturous, often draining the drama from what are supposed to be poignant, heartfelt interactions. And while some things are recounted a little too lavishly—the author will stop for pages at a time to discuss this or that Martian social custom—others are suspiciously light on details, such as the flying battleships which drop matter-of-factly into the story without so much as a paragraph of description.

Character-wise, there’s only so much to work with. Dejah Thoris is wooden, there to look pretty and play hard-to-get with the protagonist, which is par for the course with pulp sci-fi of this era. The 1910s were not exactly a high point of feminism. Tars Tarkas is more memorable as a Green Martian who rejects his culture’s cold brutishness, and tries to lead his people towards a more humane future in alliance with the Red Martians. John Carter himself has a certain likeability about him, even if he fought for the wrong side of the Civil War, and for a book filled with so much combat, his most important contributions to the world of Barsoom have to do with showing kindness.

My overall assessment? I enjoyed reading A Princess of Mars. Someday I intend to visit the sequels, of which there are several, but for now I’m satisfied with having sampled the series and the genre. Exotic vistas and over-the-top escapades have their charm; the general atmosphere of pulpiness doesn’t detract too much. If you’re in the mood for a light, silly, old-fashioned adventure, I would definitely consider this one.

Rating: 7/10. Sweeping imagination makes up for frustratingly stiff writing.

- They lay eggs, despite their overwhelmingly human-like anatomy. The contradiction is not explained or explored. ↩︎

Discover more from Let's Get Off This Rock Already!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.